www.kaichenblog.blogspot.com

www.kaichenblog.blogspot.com 陈凯一语 Kai Chen's Words:

Unity, not Liberty, is what the Chinese worship. And because of this mindless/soulless obsession, the Chinese are still trapped/mired in the abyss of despotism. What a culture values shows the nature of the culture. The Chinese culture is still, in nature, despotic and nihilistic. --- Kai Chen

团结统一,而不是自由尊严,一直是中国的人们崇拜的伪价值。 正因为这种无理无灵的迷恋,中国的人们今天仍旧摆脱不了专制奴役的桎捁。 一个文化崇拜什么暴露了这个文化的性质。 中国文化,从性质上说,仍旧是虚无与专制的。 --- 陈凯

金鐘︰ 团结-過時的口號、封建的口號 Unity-An Outdated/Despotic Slogan

作者 : 金鐘 2009-09-01 1:00 AM

今年十一,是中共建國六十周年。 每逢此時,人們都會看到天安門的燈光,看到無處不在的兩個口號︰「中華人民共和國萬歲!各族人民大團結萬歲!」過去中共中央 每年五一、十一都要發布口號。一九五一年毛澤東親自在五一口號中加上「毛主席萬歲」,到了文革,就變成了「萬歲萬歲萬萬歲」。當然還少不了「中國共產黨萬 歲」。 今天,毛萬歲不喊了,其他萬歲依舊,山呼萬歲,從來沒有受到過質疑。 雖然毛只活了八十二,沒有「萬壽無疆」,他說共產黨也和人一樣「到老年就要死 亡」,而甦聯老大哥也只活到古來稀,七十四歲。「萬歲」只不過是一個口號治國的音符。

近年中國的民族問題凸顯,矛盾激化,令人想起「各族人民大團結萬歲」這個司空見慣的口號。「團結」二字,在共產黨的字典里已經是天經地義、政治正確。 記得一 九六九年中共九大上,共產黨己經被毛整得七暈八素,他居然還說九大是一個「團結的大會、勝利的大會」。 相反,分裂就成為罪大惡極。鬧宗派,不同意見,乃至 趙紫陽反對鎮壓學生都是分裂大罪。 達賴喇嘛、熱比婭、李登輝、陳水扁,當然就更是分裂祖國的罪魁禍首。 最近達賴喇嘛被邀訪台祈福,馬總統都不敢反對,中共 (宗教局長葉小文)就敢罵他「外來和尚假念經」。 國台辦早已宣稱「反共是人民內部矛盾」,分裂祖國便是敵我矛盾。

「團結」真有那麼神聖嗎? 在我們崇尚的普世價值中有民主、自由、人權、法制、博愛、平等一系列觀念,也有多元、包容、尊重少數等內涵,沒有所謂團結。 團結誠非貶義詞,但是,抱歉,它已經被共產黨糟踏成為專制獨裁的工具和旗幟。 從馬克思《共產黨宣言》號召「全世界無產者聯合起來」,到中共革命的三大法寶之一「統 一戰線」;從毛玩弄「團結/斗爭」的權術到鄧後時代的「與中央保持一致」,意識形態的「主旋律」,「和諧社會」,都是團結的濫觴。 實質上,在一個極權體制下號召團結在共產黨周圍,接受一黨專政,這種團結無異于接受奴役,逆來順受;若想脫離這種專制,便成為分裂主義,分裂份子。 所謂統戰,引君入甕的悲劇已是屢見不鮮。 因此,在沒有政治民主、個人自由和人權保障的社會提出各民族大團結,就是一個虛偽的欺騙性的口號。 請問,在一個將民族問題當作階級斗爭對待的國家里,在一個和平執政60年拒不還政于民的制度里,民族團結還有什麼意義?

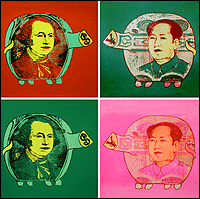

人們常將西方國家稱為自由社會,和共產黨的鐵幕社會相對比,殊不知是包含了兩種價值觀的根本對立,民主制度尊重個人和個人主義,尊重聯合與分離的自主權。 鐵幕社會則是集體主義,個人只是一個螺絲釘,團結便是捆綁群體的繩索。 追求自由,就談不上「大團結」。 因此,中共專利的「萬歲」,也到該拋棄的時候了。 這個腐朽不堪的詞令,源于對君主帝王的崇拜,也被革命狂飆所借用,和現代意識毫無相容之處(當代民主國家都不使用「萬歲」一詞表示對國家的崇拜)。 然而,「萬歲」被毛共高度揮霍之後,國人竟有麻木不仁者,甘于匍匐在「萬歲」的淫威之下做順民,其愚不可及,不啻為最大的中國特色。 到了民主化那一天,中國人要做的第一件事,就是把那個暴君之像及其萬歲裝飾,掃進歷史的垃圾堆。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

A bleak anniversary : Mao the mass murderer

A bleak anniversary : Mao the mass murdererBy Jonathan Mirsky

Published: Friday, January 9, 2003

While China celebrates the 110th anniversary of Mao Zedong's birth, six well-known Chinese intellectuals have called for his body to be removed from the mausoleum that dominates Tiananmen Square.

For Yu Jie and Liu Xiaobo, who live in Beijing — the other four live in American exile — this must be one of the bravest statements since the Communist Party seized power in 1949. In the most recent issue of the Hong Kong magazine Kaifang, or Open, they urge that sending Mao's body back to his home village in Hunan province "would elevate the status of Beijing into that of a civilized capital, and make it fit to stage a 'civilized Olympics' in 2008. We certainly do not want to see the farce of the Olympic flag flying over a city in which a corpse is worshipped."

But China's leadership has yet to come to terms with what Mao did to the country. In 1981, in a judgment overseen by Deng Xiaoping, the Communist Party admitted that Mao bore the chief responsibility for China's greatest modern catastrophe, the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, but emphasized that his "mistakes" were those of "a great revolutionary" whose contributions were far greater than his errors.

This explains why a huge portrait of Mao continues to hang over the Tiananmen walls and why, in late December, an avalanche of praise for Mao filled the Chinese media. The China Daily, an official English-language newspaper, asserted that Mao's military, philosophical and literary teachings still influence China, while according to the party's People's Daily, "His outstanding achievements, glorious ideas and great charisma influence generation after generation, far beyond his own day."

It is impossible to imagine official homage in Germany for Hitler or in Russia for Stalin. And yet Mao was a destroyer of the same class as Hitler and Stalin. He exhibited his taste for killing from the early 1930's, when, historians now estimate, he had thousands of his political adversaries slaughtered. Ten years later, still before the Communist victory, more were executed at his guerrilla headquarters at Yan'an.

Hundreds of thousands of landlords were exterminated in the early 1950's. From 1959 to 1961 probably 30 million people died of hunger — the party admits 16 million — when Mao's economic fantasies were causing peasants to starve and he purged those who warned him of the scale of the disaster.

Many more perished during the Cultural Revolution, when Mao established a special unit, supervised by Prime Minister Zhou Enlai, to report to him in detail the sufferings of hundreds of imprisoned leaders who had incurred the chairman's displeasure.

One of the chairman's secretaries, Li Rui, wrote recently, "Mao was a person who did not fear death, and he did not care how many were killed." The writers of the Kaifang article tell us what this meant for China: "Mao instilled in people's minds a philosophy of cruel struggle and revolutionary superstition. Hatred took the place of love and tolerance; the barbarism of 'It is right to rebel!' became the substitute for rationality and love of peace. It elevated and sanctified the view that relations between human beings are best characterized as those between wolves."

It is common in academic circles, not only in China but in the West, to consider Mao as a thinker, guerrilla leader, poet, calligrapher and literary theorist. Mao specialists tend to divide his career into two periods: before 1957, when Mao "the visionary" fought his way with tenacity and brilliance to party leadership and set about transforming China from a fragmented, backward society into a unified nation; and after 1957, in which Mao became power-crazed and dragged China into violence and economic stagnation.

The signatories of the Kaifang broadside, however, see Mao whole: "Under Mao, the ideological obsession with 'attacking feudalism, capitalism and revisionism' severed links with traditional Chinese culture, with modern Chinese culture and with Western civilization, deliberately placing the country beyond the mainstream of human civilization."

This seems reasonable. Yet few of Mao's closest comrades, or their successors today, ever admitted publicly, even after his death, that from his earliest years of authority whatever Mao proposed, encouraged or commanded was underpinned by the threat of death. This was also the secret of Stalin's power, and of Hitler's. The Kaifang writers note that "Mao Zedong's writings poisoned the soul and the language of the Chinese race; and his violent, hate-filled, loutish language remains a problem to this day."

In 1973 Mao suggested, apropos of Hitler, that the more people a leader kills, the more people will desire to make revolution. Mao would have approved the killing of unarmed protesters in spring 1989 not only in Tiananmen but in dozens of cities throughout China, and would have hailed the party's "hate-filled" insistence to this day that the 1989 demonstrators were criminals who deserved what they got.

At a recent American seminar on Mao a professor from Beijing who specializes in Mao studies asked me if I was suggesting that the millions of Chinese who admire and love Mao are revering a mass killer. I replied that such veneration was China's tragedy.

*

The writer is former East Asia editor of The Times of London.

No comments:

Post a Comment