陈凯一语:

Ross Terrill is one of the scholar on China who is not bought by the Chinese regime. I respect his many views for they are closer to reality and truth than many China scholars whose only purpose is to make a living by pleasing the Chinese regime. --- Kai Chen

Ross Terrill 是一个值得我尊敬的中国事物专家。 他不是那种为了生计而取悦于中共政权的人。他用诚实的个人观点赢得了我的尊敬。 --- 陈凯

Ross Terrill, The New Chinese Empire — and what it means for the United States 书/新中华帝国

http://www.amazon.com/New-Chinese-Empire-United-States/dp/0465084133/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1245251741&sr=1-1

New York, Basic Books, 2003, 384 p.

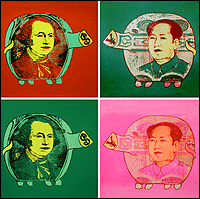

1 Ross Terrill’s point of departure is the observation that China has remained, up to now, a repressive empire devoid of any opposition. Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and now Hu Jintao, each in their own way and in their own time, have adapted and even modernised the forms of power of the thousand-year-old empire. To the author, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has maintained an imperial concept of itself and reinvented the thousand-year-old autocracy.

2 Ross Terrill is a political commentator, but also a historian; in his view, this enormous state—the only one of its kind today—is unsuited to the modern conditions of development and of unity in diversity, which are characteristic of the new century. The regime, which is both imperial and Leninist, is sticking rigidly to its obession with “stability” and “unity”: it rejects any political evolution and refuses all heterodoxy. The author does not believe that a repressive state which is opposed to progress can maintain itself for long, while the economy and society are evolving rapidly.

3 Three essential traits are said to characterise the Chinese state: it is led from the top; it believes itself to be the possessor and defender of the truth; and it makes only tactical compromises with internal and external realities. The problem is not China’s increasing power, but that it is still governed by an imperial-Leninist dictatorship. Theoretically, federalism could be a solution, and many Chinese thinkers have suggested such a constitutional structure. But the centre imposes unity by force and stability by the refusal to countenance any opposition—albeit regional—; federalism, moreover, is evidently not on the agenda.

4 Ross Terrill’s book is a reflection on Chinese history. Following a chronological plan, the author’s reflections focus first of all on how the imperial state came into being in Antiquity. In the first centuries of our era (during the Han and Tang dynasties) grew a feeling of the superiority of Chinese civilisation. The Empire believed it had a mandate to govern the Universe, even if the “barbarians” had to be “reined in” rather than overcome. At the same time, pragmatism already often got the upper hand over official doctrine, Confucianism or legism.

5 In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the tragic decline of China illustrated the search for a new political order, and, in the main, the failure of such efforts. The coming of Mao Zedong was that of a “Red Emperor”, a name the author also applies to Deng Xiaoping and to Jiang Zemin. The Party-state’s Number One, who is not elected by the people, has conserved—although in a decreasing manner—the tributes, prejudices, constraints and characteristics of the Sons of Heaven. The era of Deng and Jiang is attempting a synthesis, which the author sees as impossible, between Leninism and the market economy.

6 New questions arise in the context of the modern world. What is China? Where are its frontiers, if it has any? What does being Chinese mean? Several chapters follow, which focus on the relationships between the mainland and its maritime extensions—Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Pacific; and Central Asia—Tibet, Xinjiang, Mongolia. These reflections provide stimulating passages about Chinese foreign policy, “its aims and its imperial ways of acting”.

7 Looking to the future, Ross Terrill lists the main challenges he believes China must face. First of all, an ageing population: a quarter of Chinese will be over 65 in 2030. Relations between civilian and military leaders may cause political problems. The health system in rural areas remains highly inadequate. The traditional political apathy of the majority of Chinese can only favour an oligarchical regime. The problems of legitimacy and of succession to power are not resolved by the compulsory adherence to the “four cardinal principles” (the socialist road, the dictatorship of the proletariat, government by the Communist Party, and Marxism-Leninism) which “are in practice the unofficial Constitution of the PRC”. Scientific and technical creativity needs to be expanded. The banking system needs to be overhauled. The environment still needs cleaning up. Some items on this list are questionable, while other challenges could be added to it. Ross Terrill foresees a collapse of the system rather than a gradual evolution. However, one does not always see clearly, in his conclusion, what comes under geopolitical analysis and what stems from the opinions of a militant democrat.

8 The book ends by conjuring up seven possible scenarios. The first is the continuity of the present state of affairs. The second is of a weakening of the centre and of a certain regional fragmentation. The third envisages a partial evolution towards a multiparty system. The fourth hypothesis is that of a quiet collapse of the Communist Party, comparable to what happened in Moscow in 1991. The fifth hypothesis has the author envisaging a split in the Party between Leninists and Social Democrats ; the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) intervenes in favour of the former and then goes back to barracks. Two additional developments could take the place of this scenario : either the PLA seizes power, or, on the contrary, it supports the Social Democrat wing and the system begins to move towards a postcommunist regime. Some will say this is excess of imagination and total uncertainty.

9 Ross Terrill has put all his talent into this remarkable book which is, nevertheless, a work which expounds a thesis: the present “imperial-Leninist” Chinese regime is incompatible with the market economy and unsuited to the changes of the beginning of the twenty-first century. It is likely to disappear in sudden collapse rather than by gradual evolution.

10 All political regimes do indeed come to an end, and that of the Chinese Party-state will meet this fate sooner or later. However, certain factors do not seem to have been sufficiently taken into account by the author, in particular the size of the Chinese population. It is a pity that the book does not devote a chapter to demographic history, which would shed essential light. The population of China (22% of humanity) is an exceptional and historically unprecedented element. Because of its mass, and its inequalities of development, it seems unlikely to us that China could evolve politically according to the model of Taiwan, of South Korea or even of twentieth century Japan.

11 Moreover one can disagree with some of the author’s other beliefs. The postulate according to which a Leninist regime is incompatible with a market economy is not demonstrated. Politics often consists of circumventing incompatibilities, of reconciling opposites and of finding compromises which a priori seemed impossible. The group of practising engineers which governs in Peking is perhaps incapable of doing more than managing the country in a period of seething and destabilising economic growth. But would their possible replacements do any better?

12 Finally, the book adheres to a very monolithic vision of the present political system. There is no room for the appearance of trends, whether reforming or conservative. It is true that the obsession with “stability” and “unity” at the summit of the Party-state keeps them at bay. But their underlying existence is also attested by this obsession. And socio-economic evolution, the appearance of new social groups, as well as the relative weakening of the central government, are fertile ground for their development.

No comments:

Post a Comment