The Collapse of Soviet Empire 苏联党奴朝的解体

陈凯博客: www.kaichenblog.blogspot.com 陈凯一语: Kai Chen's Words: “道德纤维”是粘结、编制一个社会的基点。 任何的专制社会都是靠强力压挤成的“奴体”。 里根的“邪恶帝国”的清晰道德审定加速了苏联的人们对自身所处的邪恶社会的理解。 我只希望今天的美国会有另一个里根对中国党奴朝作出同样的道德审定。 “Moral Fibers" are the essential element in forming a legitimate society. All despotic societies are formed by the external pressure from government's tyrannical power. They are thus not nations but slave states. Ronald Reagan's moral judgment toward USSR as "Evil Empire" accelerated the moral/spiritual awakening of the people in such a despotic society (USSR). I only hope today there will be another Ronald Reagan coming out to declare China as the "Evil Party-Dynasty". ----------------------------------------------------------------- Everything You Think You Know About the Collapse of the Soviet Union Is Wrong “苏联解体”的真实原因 - 缺少道德与意义感 *And why it matters today in a new age of revolution. BY LEON ARON |JULY/AUGUST 2011 Every revolution is a surprise. Still, the latest Russian Revolution must be counted among the greatest of surprises. In the years leading up to 1991, virtually no Western expert, scholar, official, or politician foresaw the impending collapse of the Soviet Union, and with it one-party dictatorship, the state-owned economy, and the Kremlin's control over its domestic and Eastern European empires. Neither, with one exception, did Soviet dissidents nor, judging by their memoirs, future revolutionaries themselves. When Mikhail Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist Party in March 1985, none of his contemporaries anticipated a revolutionary crisis. Although there were disagreements over the size and depth of the Soviet system's problems, no one thought them to be life-threatening, at least not anytime soon. Whence such strangely universal shortsightedness? The failure of Western experts to anticipate the Soviet Union's collapse may in part be attributed to a sort of historical revisionism -- call it anti-anti-communism -- that tended to exaggerate the Soviet regime's stability and legitimacy. Yet others who could hardly be considered soft on communism were just as puzzled by its demise. One of the architects of the U.S. strategy in the Cold War, George Kennan, wrote that, in reviewing the entire "history of international affairs in the modern era," he found it "hard to think of any event more strange and startling, and at first glance inexplicable, than the sudden and total disintegration and disappearance … of the great power known successively as the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union." Richard Pipes, perhaps the leading American historian of Russia as well as an advisor to U.S. President Ronald Reagan, called the revolution "unexpected." A collection of essays about the Soviet Union's demise in a special 1993 issue of the conservative National Interest magazine was titled "The Strange Death of Soviet Communism." Were it easier to understand, this collective lapse in judgment could have been safely consigned to a mental file containing other oddities and caprices of the social sciences, and then forgotten. Yet even today, at a 20-year remove, the assumption that the Soviet Union would continue in its current state, or at most that it would eventually begin a long, drawn-out decline, seems just as rational a conclusion. Indeed, the Soviet Union in 1985 possessed much of the same natural and human resources that it had 10 years before. Certainly, the standard of living was much lower than in most of Eastern Europe, let alone the West. Shortages, food rationing, long lines in stores, and acute poverty were endemic. But the Soviet Union had known far greater calamities and coped without sacrificing an iota of the state's grip on society and economy, much less surrendering it. Nor did any key parameter of economic performance prior to 1985 point to a rapidly advancing disaster. From 1981 to 1985 the growth of the country's GDP, though slowing down compared with the 1960s and 1970s, averaged 1.9 percent a year. The same lackadaisical but hardly catastrophic pattern continued through 1989. Budget deficits, which since the French Revolution have been considered among the prominent portents of a coming revolutionary crisis, equaled less than 2 percent of GDP in 1985. Although growing rapidly, the gap remained under 9 percent through 1989 -- a size most economists would find quite manageable. The sharp drop in oil prices, from $66 a barrel in 1980 to $20 a barrel in 1986 (in 2000 prices) certainly was a heavy blow to Soviet finances. Still, adjusted for inflation, oil was more expensive in the world markets in 1985 than in 1972, and only one-third lower than throughout the 1970s. And at the same time, Soviet incomes increased more than 2 percent in 1985, and inflation-adjusted wages continued to rise in the next five years through 1990 at an average of over 7 percent. Yes, the stagnation was obvious and worrisome. But as Wesleyan University professor Peter Rutland has pointed out, "Chronic ailments, after all, are not necessarily fatal." Even the leading student of the revolution's economic causes, Anders Åslund, notes that from 1985 to 1987, the situation "was not at all dramatic." From the regime's point of view, the political circumstances were even less troublesome. After 20 years of relentless suppression of political opposition, virtually all the prominent dissidents had been imprisoned, exiled (as Andrei Sakharov had been since 1980), forced to emigrate, or had died in camps and jails. There did not seem to be any other signs of a pre-revolutionary crisis either, including the other traditionally assigned cause of state failure -- external pressure. On the contrary, the previous decade was correctly judged to amount "to the realization of all major Soviet military and diplomatic desiderata," as American historian and diplomat Stephen Sestanovich has written. Of course, Afghanistan increasingly looked like a long war, but for a 5-million-strong Soviet military force the losses there were negligible. Indeed, though the enormous financial burden of maintaining an empire was to become a major issue in the post-1987 debates, the cost of the Afghan war itself was hardly crushing: Estimated at $4 billion to $5 billion in 1985, it was an insignificant portion of the Soviet GDP. Nor was America the catalyzing force. The "Reagan Doctrine" of resisting and, if possible, reversing the Soviet Union's advances in the Third World did put considerable pressure on the perimeter of the empire, in places like Afghanistan, Angola, Nicaragua, and Ethiopia. Yet Soviet difficulties there, too, were far from fatal. As a precursor to a potentially very costly competition, Reagan's proposed Strategic Defense Initiative indeed was crucial -- but it was far from heralding a military defeat, given that the Kremlin knew very well that effective deployment of space-based defenses was decades away. Similarly, though the 1980 peaceful anti-communist uprising of the Polish workers had been a very disturbing development for Soviet leaders, underscoring the precariousness of their European empire, by 1985 Solidarity looked exhausted. The Soviet Union seemed to have adjusted to undertaking bloody "pacifications" in Eastern Europe every 12 years -- Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, Poland in 1980 -- without much regard for the world's opinion. This, in other words, was a Soviet Union at the height of its global power and influence, both in its own view and in the view of the rest of the world. "We tend to forget," historian Adam Ulam would note later, "that in 1985, no government of a major state appeared to be as firmly in power, its policies as clearly set in their course, as that of the USSR." Certainly, there were plenty of structural reasons -- economic, political, social -- why the Soviet Union should have collapsed as it did, yet they fail to explain fully how it happened when it happened. How, that is, between 1985 and 1989, in the absence of sharply worsening economic, political, demographic, and other structural conditions, did the state and its economic system suddenly begin to be seen as shameful, illegitimate, and intolerable by enough men and women to become doomed? LIKE VIRTUALLY ALL modern revolutions, the latest Russian one was started by a hesitant liberalization "from above" -- and its rationale extended well beyond the necessity to correct the economy or make the international environment more benign. The core of Gorbachev's enterprise was undeniably idealistic: He wanted to build a more moral Soviet Union. For though economic betterment was their banner, there is little doubt that Gorbachev and his supporters first set out to right moral, rather than economic, wrongs. Most of what they said publicly in the early days of perestroika now seems no more than an expression of their anguish over the spiritual decline and corrosive effects of the Stalinist past. It was the beginning of a desperate search for answers to the big questions with which every great revolution starts: What is a good, dignified life? What constitutes a just social and economic order? What is a decent and legitimate state? What should such a state's relationship with civil society be? "A new moral atmosphere is taking shape in the country," Gorbachev told the Central Committee at the January 1987 meeting where he declared glasnost -- openness -- and democratization to be the foundation of his perestroika, or restructuring, of Soviet society. "A reappraisal of values and their creative rethinking is under way." Later, recalling his feeling that "we couldn't go on like that any longer, and we had to change life radically, break away from the past malpractices," he called it his "moral position." In a 1989 interview, the "godfather of glasnost," Aleksandr Yakovlev, recalled that, returning to the Soviet Union in 1983 after 10 years as the ambassador to Canada, he felt the moment was at hand when people would declare, "Enough! We cannot live like this any longer. Everything must be done in a new way. We must reconsider our concepts, our approaches, our views of the past and our future.… There has come an understanding that it is simply impossible to live as we lived before -- intolerably, humiliatingly." To Gorbachev's prime minister Nikolai Ryzhkov, the "moral [nravstennoe] state of the society" in 1985 was its "most terrifying" feature: [We] stole from ourselves, took and gave bribes, lied in the reports, in newspapers, from high podiums, wallowed in our lies, hung medals on one another. And all of this -- from top to bottom and from bottom to top. Another member of Gorbachev's very small original coterie of liberalizers, Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze, was just as pained by ubiquitous lawlessness and corruption. He recalls telling Gorbachev in the winter of 1984-1985: "Everything is rotten. It has to be changed." Back in the 1950s, Gorbachev's predecessor Nikita Khrushchev had seen firsthand how precarious was the edifice of the house that Stalin built on terror and lies. But this fifth generation of Soviet leaders was more confident of the regime's resilience. Gorbachev and his group appeared to believe that what was right was also politically manageable. Democratization, Gorbachev declared, was "not a slogan but the essence of perestroika." Many years later he told interviewers: The Soviet model was defeated not only on the economic and social levels; it was defeated on a cultural level. Our society, our people, the most educated, the most intellectual, rejected that model on the cultural level because it does not respect the man, oppresses him spiritually and politically. That reforms gave rise to a revolution by 1989 was due largely to another "idealistic" cause: Gorbachev's deep and personal aversion to violence and, hence, his stubborn refusal to resort to mass coercion when the scale and depth of change began to outstrip his original intent. To deploy Stalinist repression even to "preserve the system" would have been a betrayal of his deepest convictions. A witness recalls Gorbachev saying in the late 1980s, "We are told that we should pound the fist on the table," and then clenching his hand in an illustrative fist. "Generally speaking," continued the general secretary, "it could be done. But one does not feel like it." THE ROLE OF ideas and ideals in bringing about the Russian revolution comes into even sharper relief when we look at what was happening outside the Kremlin. A leading Soviet journalist and later a passionate herald of glasnost, Aleksandr Bovin, wrote in 1988 that the ideals of perestroika had "ripened" amid people's increasing "irritation" at corruption, brazen thievery, lies, and the obstacles in the way of honest work. Anticipations of "substantive changes were in the air," another witness recalled, and they forged an appreciable constituency for radical reforms. Indeed, the expectations that greeted the coming to power of Gorbachev were so strong, and growing, that they shaped his actual policy. Suddenly, ideas themselves became a material, structural factor in the unfolding revolution. The credibility of official ideology, which in Yakovlev's words, held the entire Soviet political and economic system together "like hoops of steel," was quickly weakening. New perceptions contributed to a change in attitudes toward the regime and "a shift in values." Gradually, the legitimacy of the political arrangements began to be questioned. In an instance of Robert K. Merton's immortal "Thomas theorem" -- "If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequence" -- the actual deterioration of the Soviet economy became consequential only after and because of a fundamental shift in how the regime's performance was perceived and evaluated. Writing to a Soviet magazine in 1987, a Russian reader called what he saw around him a "radical break [perelom] in consciousness." We know that he was right because Russia's is the first great revolution whose course was charted in public opinion polls almost from the beginning. Already at the end of 1989, the first representative national public opinion survey found overwhelming support for competitive elections and the legalization of parties other than the Soviet Communist Party -- after four generations under a one-party dictatorship and with independent parties still illegal. By mid-1990, more than half those surveyed in a Russian region agreed that "a healthy economy" was more likely if "the government allows individuals to do as they wish." Six months later, an all-Russia poll found 56 percent supporting a rapid or gradual transition to a market economy. Another year passed, and the share of the pro-market respondents increased to 64 percent. Those who instilled this remarkable "break in consciousness" were no different from those who touched off the other classic revolutions of modern times: writers, journalists, artists. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed, such men and women "help to create that general awareness of dissatisfaction, that solidified public opinion, which … creates effective demand for revolutionary change." Suddenly, "the entire political education" of the nation becomes the "work of its men of letters." And so it was in Soviet Russia. The lines to newspaper kiosks -- sometimes crowds around the block that formed at six in the morning, with each daily run often sold out in two hours -- and the skyrocketing subscriptions to the leading liberal newspapers and magazines testify to the devastating power of the most celebrated essayists of glasnost, or in Samuel Johnson's phrase, the "teachers of truth": the economist Nikolai Shmelyov; the political philosophers Igor Klyamkin and Alexander Tsypko; brilliant essayists like Vasily Selyunin, Yuri Chernichenko, Igor Vinogradov, and Ales Adamovich; the journalists Yegor Yakovlev, Len Karpinsky, Fedor Burlatsky, and at least two dozen more. To them, a moral resurrection was essential. This meant not merely an overhaul of the Soviet political and economic systems, not merely an upending of social norms, but a revolution on the individual level: a change in the personal character of the Russian subject. As Mikhail Antonov declared in a seminal 1987 essay, "So What Is Happening to Us?" in the magazine Oktyabr, the people had to be "saved" -- not from external dangers but "most of all from themselves, from the consequences of those demoralizing processes that kill the noblest human qualities." Saved how? By making the nascent liberalization fateful, irreversible -- not Khrushchev's short-lived "thaw," but a climate change. And what would guarantee this irreversibility? Above all, the appearance of a free man who would be "immune to the recurrences of spiritual slavery." The weekly magazine Ogoniok, a key publication of glasnost, wrote in February 1989 that only "man incapable of being a police informer, of betraying, and of lies, no matter in whose or what name, can save us from the re-emergence of a totalitarian state." The circuitous nature of this reasoning -- to save the people one had to save perestroika, but perestroika could be saved only if it was capable of changing man "from within" -- did not seem to trouble anyone. Those who thought out loud about these matters seemed to assume that the country's salvation through perestroika and the extrication of its people from the spiritual morass were tightly -- perhaps, inextricably -- interwoven, and left it at that. What mattered was reclaiming the people to citizenship from "serfdom" and "slavery." "Enough!" declared Boris Vasiliev, the author of a popular novella of the period about World War II, which was made into an equally well-received film. "Enough lies, enough servility, enough cowardice. Let's remember, finally, that we are all citizens. Proud citizens of a proud nation!" DELVING INTO THE causes of the French Revolution, de Tocqueville famously noted that regimes overthrown in revolutions tend to be less repressive than the ones preceding them. Why? Because, de Tocqueville surmised, though people "may suffer less," their "sensibility is exacerbated." As usual, Tocqueville was onto something hugely important. From the Founding Fathers to the Jacobins and Bolsheviks, revolutionaries have fought under essentially the same banner: advancement of human dignity. It is in the search for dignity through liberty and citizenship that glasnost's subversive sensibility lives -- and will continue to live. Just as the pages of Ogoniok and Moskovskie Novosti must take pride of place next to Boris Yeltsin on the tank as symbols of the latest Russian revolution, so should Internet pages in Arabic stand as emblems of the present revolution next to the images of rebellious multitudes in Cairo's Tahrir Square, the Casbah plaza in Tunis, the streets of Benghazi, and the blasted towns of Syria. Languages and political cultures aside, their messages and the feelings they inspired were remarkably similar. The fruit-seller Mohamed Bouazizi, whose self-immolation set off the Tunisian uprising that began the Arab Spring of 2011, did so "not because he was jobless," a demonstrator in Tunis told an American reporter, but "because he … went to talk to the [local authorities] responsible for his problem and he was beaten -- it was about the government." In Benghazi, the Libyan revolt started with the crowd chanting, "The people want an end to corruption!" In Egypt, the crowds were "all about the self-empowerment of a long-repressed people no longer willing to be afraid, no longer willing to be deprived of their freedom, and no longer willing to be humiliated by their own leaders," New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman reported from Cairo this February. He could have been reporting from Moscow in 1991. "Dignity Before Bread!" was the slogan of the Tunisian revolution. The Tunisian economy had grown between 2 and 8 percent a year in the two decades preceding the revolt. With high oil prices, Libya on the brink of uprising also enjoyed an economic boom of sorts. Both are reminders that in the modern world, economic progress is not a substitute for the pride and self-respect of citizenship. Unless we remember this well, we will continue to be surprised -- by the "color revolutions" in the post-Soviet world, the Arab Spring, and, sooner or later, an inevitable democratic upheaval in China -- just as we were in Soviet Russia. "The Almighty provided us with such a powerful sense of dignity that we cannot tolerate the denial of our inalienable rights and freedoms, no matter what real or supposed benefits are provided by 'stable' authoritarian regimes," the president of Kyrgyzstan, Roza Otunbayeva, wrote this March. "It is the magic of people, young and old, men and women of different religions and political beliefs, who come together in city squares and announce that enough is enough." Of course, the magnificent moral impulse, the search for truth and goodness, is only a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the successful remaking of a country. It may be enough to bring down the ancien regime, but not to overcome, in one fell swoop, a deep-seated authoritarian national political culture. The roots of the democratic institutions spawned by morally charged revolutions may prove too shallow to sustain a functioning democracy in a society with precious little tradition of grassroots self-organization and self-rule. This is something that is likely to prove a huge obstacle to the carrying out of the promise of the Arab Spring -- as it has proved in Russia. The Russian moral renaissance was thwarted by the atomization and mistrust bred by 70 years of totalitarianism. And though Gorbachev and Yeltsin dismantled an empire, the legacy of imperial thinking for millions of Russians has since made them receptive to neo-authoritarian Putinism, with its propaganda leitmotifs of "hostile encirclement" and "Russia rising off its knees." Moreover, the enormous national tragedy (and national guilt) of Stalinism has never been fully explored and atoned for, corrupting the entire moral enterprise, just as the glasnost troubadours so passionately warned. Which is why today's Russia appears once again to be inching toward another perestroika moment. Although the market reforms of the 1990s and today's oil prices have combined to produce historically unprecedented prosperity for millions, the brazen corruption of the ruling elite, new-style censorship, and open disdain for public opinion have spawned alienation and cynicism that are beginning to reach (if not indeed surpass) the level of the early 1980s. One needs only to spend a few days in Moscow talking to the intelligentsia or, better yet, to take a quick look at the blogs on LiveJournal (Zhivoy Zhurnal), Russia's most popular Internet platform, or at the sites of the top independent and opposition groups to see that the motto of the 1980s -- "We cannot live like this any longer!" -- is becoming an article of faith again. The moral imperative of freedom is reasserting itself, and not just among the limited circles of pro-democracy activists and intellectuals. This February, the Institute of Contemporary Development, a liberal think tank chaired by President Dmitry Medvedev, published what looked like a platform for the 2012 Russian presidential election: In the past Russia needed liberty to live [better]; it must now have it in order to survive.… The challenge of our times is an overhaul of the system of values, the forging of new consciousness. We cannot build a new country with the old thinking.… The best investment [the state can make in man] is Liberty and the Rule of Law. And respect for man's Dignity. It was the same intellectual and moral quest for self-respect and pride that, beginning with a merciless moral scrutiny of the country's past and present, within a few short years hollowed out the mighty Soviet state, deprived it of legitimacy, and turned it into a burned-out shell that crumbled in August 1991. The tale of this intellectual and moral journey is an absolutely central story of the 20th century's last great revolution. | |

图:1991年8月19日,叶利钦在莫斯科向民众呼吁举行全国总罢工和大规模示威。12月31日,镳刀斧头旗在克里姆林宫降下,宣告苏联共产帝国解体。 (AFP) 陈凯博客: www.kaichenblog.blogspot.com 陈凯一语: Kai Chen's Words: “道德纤维”是粘结、编制一个社会的基点。 任何的专制社会都是靠强力压挤成的“奴体”。 里根的“邪恶帝国”的清晰道德审定加速了苏联的人们对自身所处的邪恶社会的理解。 我只希望今天的美国会有另一个里根对中国党奴朝作出同样的道德审定。 “Moral Fibers" are the essential element in forming a legitimate society. All despotic societies are formed by the external pressure from government's tyrannical power. They are thus not nations but slave states. Ronald Reagan's moral judgment toward USSR as "Evil Empire" accelerated the moral/spiritual awakening of the people in such a despotic society (USSR). I only hope today there will be another Ronald Reagan coming out to declare China as the "Evil Party-Dynasty". ------------------------------------------------------------ 前苏联崩溃:你知道的每件事都错了 Everything You Know is Wrong on USSR's End 【大纪元2011年06月26日讯】 美国《外交政策》最新一期发表文章分析了前苏联的崩溃,为何全世界出现集体性误判?当时的苏联经济停滞,政治管制严厉,从各方面看都没有急剧恶化;然而似乎是不经意的,从道德审视开始,“每件事都已经腐烂,必须做出改变”,一直到政治合法性遭到诘问,全民认知的剧烈转折,才促成了前苏联的崩溃,其中道德的复活才是精髓。 当时的名言:“谎言够了,奴性够了,怯懦够了。最终,我们要记住,我们都是公民。一个骄傲国家的骄傲公民”。“每件事情都必须以一种全新的方式开始。我们必须重新考虑我们的概念,我们的思路,我们对于过去和未来的看法......无法再像过去那样生活——那是一种无法忍受的耻辱”。 文章认为,如今俄国人再次愤怒,统治精英的腐败、新式审查制度、蔑视公共舆论,总统梅德韦杰夫称:不能在旧思维上建立新国家。或许俄国“道德”问诘再次来临? 前苏联革命 最出人意料的事件 这篇题为“关于苏联的崩溃:你知道的每件事都是错的”(Everything You Think You Know About the Collapse of the Soviet Union Is Wrong)的长篇文章说,每次革命都是一次惊奇。但上一次前苏联革命却可列入最出人意料的事件之列。 时间回到1991年之前,当时在西方,无论专家、学者、官员或是政客们,都没有预料到整个苏维埃联盟及其一党独裁制度,国营经济体,以及克里姆林宫对于国内和东欧帝国的控制会在一夜间分崩离析。自视为未来革命者的苏联国内异议份子,同样也没有预计到这一点。 1985年,当米哈伊尔‧戈尔巴乔夫成为总书记时,他的同代人完全没有预计到一场革命危机的到来。虽然围绕苏联体制中存在问题的规模和深度有着各种争论,但没人想到这些麻烦会危及体制的生命,至少不会这么快。 诡异灭亡 集体性误判 而这种普遍的短视由何而来?或许某些专家倾向于夸大苏维埃政权的能力和合法性?然而,另外一些几乎完全没有对共产主义持怀疑态度的人,也对其突然死亡感到困惑。 作为美国冷战战略的设计师之一,乔治‧凯南在《当代国际事务史》中回顾这段历程时,认为“很难有比它更加诡异和出人意料,甚至乍看上去有些难以理解的事件,先后以俄罗斯帝国和苏维埃联盟面目出现的一个强大国家,顷刻间便土崩瓦解,完全消失的无影无踪”。 1993年,美国总统罗纳德‧里根的顾问之一,理查德‧帕普斯在保守的《国家利益》杂志上,发表了关于苏联死亡的论文集,题目是《苏维埃共产主义的诡异灭亡》。 经济停滞明显 但慢性病并非置人于死地 实际上,1985年的苏联,与其十年前相比拥有类似的自然及人力资源。当然,其生活标准比绝大多数东欧国家低得多,更无法与西方相比。物资短缺、食品配给、商店门口的长队,以及剧烈的贫困都是顽疾。不过,苏联经历过比这远大得多的灾难,而且没有为此牺牲哪怕一点点对于社会和经济的控制,在这一点上它们从不让步。 在1985年,没有任何关键经济数据表明这个国家会面对即将到来的灾难。与1960和1970年代相比,从1981到1985年,该国GDP虽然缓慢下降,但仍保持平均每年1.9%的正增长。这种漫不经心但很难构成灾难的增长模式,一直持续到1989 年。 不错,经济的停滞明显,令人担忧。但正如卫斯理大学教授彼得‧洛特兰德所言:“说到底,慢性病并不必然置人于死地”。即便是研究革命爆发经济根源的专家安德斯‧阿斯兰德也指出,从1985到1987年,局势“没有任何变化”。 政治:几乎所有的异见人士都被羁押 文章说,在执政者看来,政治生态甚至有所改善。经过此前二十年对政治反对派不间断的镇压之后,几乎所有突出的异见分子都已被羁押,流放,强迫移民,或是死于劳改营和监狱之中。 这个国家没有表现出任何即将爆发革命的迹象,包括其他传统上被看作国家灭亡的根源之一——外部压力。恰恰相反,之前十年间,正如美国历史与外交学家斯蒂芬‧塞斯塔诺维奇所言,他们已经“实现了所有军事和外交目标”。当然,阿富汗看上去越来越像是一场长期战争,但对于拥有五百万人的苏军来说,这点损失不过是九牛一毛。 文章认为,美国也不是催化剂。如果可能的话,“里根主义”政策逆转了苏联在第三世界的优势,给帝国周边带来了相当大压力,比如阿富汗,安哥拉,尼加拉瓜和埃塞俄比亚。然而,苏联面对的这些困难远不致其崩溃。 为何走向灭亡? 文章说,当然,就苏联为什么会崩溃,有大量结构性推论——经济、政治、社会等等,然而当这件事发生时,这些理由却全部无法解释其为何发生。1985到1989年间,无论经济、政治、人口、以及其他结构性环境,都没有发生急剧恶化,那么,这个国家及其经济体系是如何突然间被大量善男信女看作可耻、非法和不能忍受, 以至于走向灭亡呢? 就像所有现代革命一样,俄国革命始于“上层”对于自由化的迟疑——其理由已经超越了对于经济的必要调整,以及让国际环境更加有利。毫无疑问,戈尔巴乔夫的创业思路有着某种理想主义色彩:想建立一个更加有道德的苏维埃联盟。 戈尔巴乔夫:开展对价值观的重估 虽然以经济改良为旗帜 ,但戈尔巴乔夫及其支持者无疑首先修补了道德,而不是经济上的错误。他们中的绝大多数人在公开谈论这场改革时,无不对精神文明的倒退,以及斯大林主义过往的腐败影响感到痛心疾首。 如此一来,历次大革命爆发前夜曾提出过的那些问题,便再次吸引人们绝望的寻找答案:什么是有尊严的生活?构成一个公正的社会和经济的只需是什么?一个合法与正派的国家是怎样的?这样一个国家,应与其公民社会保持什么关系? “在这个国家,一层全新的道德空气正在成型”,1987年1月,在中央委员会会议中,戈尔巴乔夫讲话中指出。他当时宣布开放和民主化将成为这次俄式改革,或者说苏维埃社会重构的基础。“要开展对于价值观的重估,及对其创造性的反思”。后来,他回忆道“我们无路可走,我们必须彻底改变,与过去的失职行为划清界限”,他将其称之为自己的“道德立场”。 “够了!我们不能再这样生活下去。每件事情都必须以一种全新的方式开始。我们必须重新考虑我们的概念,我们的思路,我们对于过去和未来的看法......此时人们已经无法再像过去那 样生活——那是一种无法忍受的耻辱”,1989年的一次采访中,号称“开放教父”的亚历山大‧亚科夫列夫曾回忆。 外交部长:每件事都已经腐烂 在戈尔巴乔夫的总理尼古拉‧雷日科夫看来,1985年的“道德社会国家”有着“极为惊人”的特征:我们监守自盗,行贿受贿,无论在报纸、新闻还是讲台上,都谎话连篇,我们一面沉溺于自己的谎言,一面为彼此佩戴奖章。而且所有人都在这么干——从上到下,从下到上。 戈尔巴乔夫那个自由化小圈子的另外一名成员,外交部长爱德华‧谢瓦尔德纳则对普遍存在的目无法纪和腐败堕落痛心不已。据他回忆,1984-1985年冬天,他曾对戈尔巴乔夫讲到:“每件事都已经腐烂,必须做出改变”。 恐怖和谎言文化 全民排斥 文章说,早在1950年代,戈尔巴乔夫的先辈,尼基塔‧赫鲁晓夫也曾认为斯大林时代建立在恐怖和谎言基础上的建筑早已摇摇欲坠。但戈尔巴乔夫及其派别似乎相信,可以在保持政治可控的情况下拨乱反正。民主化,戈尔巴乔夫宣称,“不是一句口号,而是这场改革的精髓”。许多年后,他在采访中表示: 不仅在经济和社会层面,甚至在文化层面,苏联模式也已经失败。我们的社会,我们的人民,绝大多数受教育者,绝大多数知识份子,都排斥这种文化,因为它不尊重这些人,反而从精神和政治上压迫他们。 这场改革导致1989年革命,多半是出于另外一个“理想主义”理由:出于对暴力的深深厌恶,因此当改革的深度及规模超出他最初的预想时,他顽固的拒绝诉诸于大规模镇压。为了保护这个体系而采取斯大林式的镇压,是对他内心最深处某些信念的背叛。 一位著名记者,后来成为热衷开放先驱的亚历山大‧鲍文,在1988年曾写道,随着人民对腐败、无耻的偷窃、谎言,以及城市工作的妨碍越发“烦躁”,俄式改革的理想已经“成熟”。 政治上合法性遭到诘问 文章说,官方意识形态的信誉,此时正在迅速弱化,用亚科夫列夫的话说。新的认知为“价值观的转变”以及对于政权的看法改变做出贡献。逐渐的,政治上无懈可击的合法性开始遭到诘问。 在罗伯特.莫顿不朽的“托马斯定理”——如果人们把某种情景定义为真实,那么这种情景就会成为他们真实的结果——情形下,苏维埃经济的实际恶化在不久之后成为结果,并因此导致了对于这个政权的认知及评价的根本转变。 全民认知的剧烈转折 1987年,在一本苏联杂志上,一位俄国读者称在自己周围看到一种“认知的剧烈转折”。我们知道他是对的,这是首次从一开始就全程都有民意调查记录留存的大革命。 早在1989年末,第一界国民议会的公开舆论调查就发现,经过四代一档独裁统治,并且在独立党派仍然非法的情况下,竞争性选举和让俄共之外的独立党派合法化得到势不可挡的支持。1990年代中期,地区调查发现超过半数受访者认为,“一个健康的经济体”需要政府“允许个体按照自己的意愿行事”。 六个月后,一次全俄调查发现,56%受访者支持激进或渐进的市场经济改革。一年之后,赞同市场经济改革的受访者已经增加到64%。 与那些引爆其他经典现代革命的人相比,传播这类“认识转变”的人们并无不同:作家、记者和艺术家。正如亚历克西‧德‧托克维尔所言,这些男男女女“帮助创造了那些普遍的不满意识,那些凝固的公众舆论......并由此创造了对于革命变革的有效需求”。 因此,这是在苏维埃俄国。卖报亭前排队的长龙——每天早上六点就开始排起长队,每天的报纸两小时之内便被一扫而空——以及著名自由化报刊杂志的销量猛增,证实了话语权开始转向绝大多数开放论点作者。 道德的复活才是精髓 文章说,对他们来说,道德的复活才是精髓。此时,苏维埃的政治经济体系并未要求得到彻底更新,社会准则也没有完全颠覆的要求,但在个体水平上,革命已经发生:俄国人品质的变化。 1987年,在《红十月》杂志一篇广为传颂的文章中,米哈伊尔‧安托诺夫宣布,“那么,我们身边正在发生什么?”人民必须得到“拯救”—— 不是因为来自外部的危险,而是因为它们“被他们自己,被那些道德败坏的行为扼杀了高贵的人类本性”。怎样拯救?通过初生的,不可逆转的自由化——不是赫鲁晓夫那短命的“缓和”,而是整个气候的改变。怎样保证这种改变无法逆转?首先,已经获得自由的人,将“对再次成为精神奴隶免疫”。 作为俄国改革开放的重要刊物,《红十月》在1989年2月的一篇文章中写到,只要“人不做告密者,不背信弃义,不言不由衷,无论他是谁,是什么名字,都可以从这个极权主义国家中拯救我们”。 当务之急是把人民从“奴隶”和“农奴”改造为公民。“够了!”著名二战小说家鲍里斯‧瓦西列夫宣布。“谎言够了,奴性够了, 怯懦够了。最终,我们要记住,我们都是公民。一个骄傲国家的骄傲公民”。 不能容忍自己的权利和自由遭到剥夺 水果小贩穆哈迈德‧布拉齐齐的自我牺牲,引发了突尼斯起义,那是2011年阿拉伯之春的起点,“尊严高于面包!”这是突尼斯革命的口号。 就像对苏维埃俄国那样。“无论‘不可一世的’集权政权为我们提供任何或真或假的好处,上帝赐予我们的尊严令我们不能容忍自己的权利和自由遭到剥夺”,吉尔吉斯斯坦总统奥通巴耶娃今年三月写到。“这就像魔法一样,无论男女老幼,或者有着不同的宗教和政治信仰,人民会汇集在城市广场,宣布自己已经忍无可忍”。 俄国人再次愤怒 “道德”改革再来临? 文章说,戈尔巴乔夫和叶利钦虽然肢解了一个帝国,但帝国思想的遗产让千百万俄国人接受了同样集权的普京主义,以及他“强敌环伺”和“俄国挺直膝盖”的主张。此外,斯大林主义的国家悲剧从未被完全清算和解,它正在俯视着整个道德事业。 尽管石油价格的高企和1990年代的市场经济改革为俄国千百万人民带来史无前例的繁荣,但统治精英的腐败行径,新式审查制度,以及对于公共舆论的公开蔑视,都已经促使社会的疏远和愤怒达到 1980年代的水平。 文章说,在莫斯科,只要花费几天时间与知识份子攀谈一下,或用更快的方式,浏览一下俄国人气最高的生活杂志博客,或是登录反对组织的站点,就可以看到那些1980 年代的警句——“我们不能再这样生活下去!”——重新成为人们的信条。自由道德的当务之急是重新焕发生机,而不仅仅是在民主活动家和知识份子的小圈子里流传。 梅德韦杰夫:不能在旧思维上建立新国家 今年二月,由梅德韦杰夫主持的自由主义智库——当代发展学会出版的一篇文章,可视作这位总统2012年参选的纲领: 过去,俄国需要自由,如今,俄国仍然需要自由......我们时代的挑战是对价值体系的彻底改革,打造新的认知。我们不能在旧思维上建立新国家。......一个国家,最好的投资是自由和法制。以及对于人类尊严的敬意。 从对这个国家过去与现在残酷的道德审视开始,知识份子对于尊严的寻求似乎同样在短短几年内挖空了强大的苏维埃政权,剥夺了他的合法性,终于在1991年 秋天,让这个燃烧殆尽的空壳粉身碎骨。 在二十世纪最后一次大革命中,这段关乎探索道义神话,绝对是其中最核心的一部份。 三天改变历史 前苏联崩溃回顾 1989年东欧各国民主浪潮风起云涌,共产党国家纷纷瓦解:11月9日柏林墙倒塌;11月17日捷克“天鹅绒革命”,以和平方式推翻捷克共产政权;12月25日,罗马尼亚共产独裁者齐奥塞思库被人民赶下台并判死刑。此时,共产帝国苏联也是危机四伏,摇摇欲坠。 1991年8月19日,一个由共产党强硬派组成的“紧急委员会”发动政变,软禁了当时主张改革的苏共总书记戈尔巴乔夫,并将坦克与军车开进莫斯科市中心,包围了莫斯科市政府与俄罗斯议会大厦。政变者宣布,戈尔巴乔夫的改革政策“已经走进了死胡同”,呼吁“恢复苏联的骄傲和荣誉。” 在巨大危机时刻,叶利钦通过广播向民众发表演说,呼吁举行全国总罢工和大规模示威,对政变予以回击。随后数十万苏联人民加入抗议的行列,上街示威与军队对恃。 叶利钦向苏军士兵喊话 :“你们已经向苏联人民发过誓,你们不能调转枪口对准人民。”在强大的民意面前,在人民的欢呼声中,坦克掉转了炮口,撤出了莫斯科。 强硬派的政变三天后破产,并永远改变了苏联的历史!叶利钦成为了国家英雄,他要求搁置共产主义者在俄罗斯的所有活动。几天后(1991年8月24日),戈尔巴乔夫辞去了苏共总书记职务,并解散了中央委员会。 1991年12月21日,原苏联的10多个加盟共和国代表开会,决定成立“独立国家联合体”。圣诞节那天,这个自1917年靠暴力夺取政权的苏维埃联邦正式瓦解。叶利钦成为俄国七十多年来第一位非共产党总统。 (责任编辑:孙蕓) 美东时间: 2011-06-25 21:56:54 PM 【万年历】 本文网址: http://www.epochtimes.com/gb/11/6/26/n3297587.htm | |

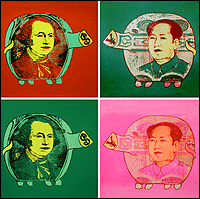

China's Red Flag by the White House 中共血旗升在白宫旁

2 comments:

Reply by Emi Da Shogun 14 hours ago

Kai Chen, I have a question since it sounds like you've had some experience living in the system in China. Here's what I don't understand: My family, well, part of my family, is currently living in Cuba and they are happy and fine and dandy with the system over there. We've tried multiple times to show them a better way, to teach them about Capitalism, how it is a better system than Communism, etc. No matter what we say, it doesn't sway them. They've been to visit us many times and it just...it comes down to the same old argument, they keep telling us that we, in fact, don't know enough to argue against their system because we haven't lived long enough within a Communist system. So...that's where I would like to ask you...how is it that there are people still living in places like China and Cuba, where Communism is, unfortunately, alive and functioning, and they are happy? If Communism is an absolute evil, shouldn't all people living in its shadow want to desperately escape it? Or are there truly completely conditioned individuals, like we suspect our family is? It saddens us to think of them like that, I mean, they ARE our family...but...could this be true? Could they just simply be...too much in the system to know any better? I appreciate any response, thanks!

Kai Chen Reply,

Dear Emi Da:

Of six billion people living on the planet earth, there are only relatively few who live in freedom. Those who are truly free are even fewer. Many Chinese who now live in the US, yearn for China's despotism, much like many on the left in Ameircan politics.

Despotism's big attraction to human beings come from its lies - lies that all human beings are fearful, evil and faithless creatures needing to be controlled by fear of men/power/guns. The brainwashing tells people all humans are corrupt and only in a communist society it has a chance to reform human nature, so as to built a "heaven on earth" by creation of "new human beings". However, the lie does not tell you that in a despotic society, human beings are conditioned to believe corruption is not only a way of life, but a wisdow, a superior culture, a kind of resourcefulness to be learned and appreciated. In other words, in a free society, corruption is viewed as corruption. In a tyranny, corruption is viewed as a virtue.

Kai Chen Reply,

Dear Emi Da:

Of six billion people living on the planet earth, there are only relatively few who live in freedom. Those who are truly free are even fewer. Many Chinese who now live in the US, yearn for China's despotism, much like many on the left in Ameircan politics.

Despotism's big attraction to human beings come from its lies - lies that all human beings are fearful, evil and faithless creatures needing to be controlled by fear of men/power/guns. The brainwashing tells people all humans are corrupt and only in a communist society it has a chance to reform human nature, so as to built a "heaven on earth" by creation of "new human beings". However, the lie does not tell you that in a despotic society, human beings are conditioned to believe corruption is not only a way of life, but a wisdow, a superior culture, a kind of resourcefulness to be learned and appreciated. In other words, in a free society, corruption is viewed as corruption. In a tyranny, corruption is viewed as a virtue.

If black is white, clarity is confusion, virtue if vice, as Marxist dialectics teaches people, then why bother to choose as an individual at all. One can just live a meaningless life as everyone else in the world. As least in a socialist state, one can hide behind crowd/government/collective to evade individual responsibilities. Socialist/despotic/tyrannical society attract slaves with false premises of safety/security/certainty - one doesn't have to look for meaning and means to live with the state providing not only means but meaning as well.

As Ayn Rand once put: Free men are only very few. But they are the unmoveable movers/the engine/the fountainhead to propell the world forward. Most people in the world, unfortunately, are slaves of their culture, their government, their own environment, their own ancestors, their own fear and uncertainty, their own lack of true identity, their own dependency on others, their own lack of will and ability to be free. So if one is free, there is no need to apologyze to anyone. Just be free, happy and creative to continue to push the world forward. Do not try to please anyone in the slave world, as Obama is trying to do. And in your case, do not try to persuade your family in Cuba to be free. They are free, being created by God. But to realize they are free and to pursue freedom, it is personal choice. Some people tend to feel very comfortable and at home when they are caged, always knowing where the food is and what the food is by their masters. They are like pigs - the fatter they get by their masters, the more likely they will be slaughtered. I hope this answers your question. It is not a happy picture. But it is reality and a true picture of our world. The important thing is not to convert others, but to live a life as a free, just and diginified individual human being. The world will be better that way.

Post a Comment