Hail Mao 毛元首万岁!

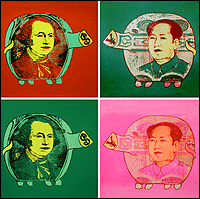

‘Pride of generation’: 1966 lithograph of Mao Zedong. The late chairman’s face has been on China’s banknotes ever since but his memory is being invoked anew by conservatives such as Bo Xilai, a main contender for the politburo standing committee. 毛泽东 - 中国人的精神皇帝 陈凯博客: www.kaichenblog.blogspot.com China: Mao and the next generation 毛泽东与中国的下一代 By Kathrin Hille and Jamil Anderlini Published: June 2 2011 20:32 Financial Times At the heart of the Chinese Communist empire, in an imposing mausoleum in the centre of Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, the body of Mao Zedong still lies in state in a glass sarcophagus 35 years after his death. Hundreds of thousands of visitors arrive annually to gaze at the waxen face of the man hailed for throwing off the yoke of foreign oppression to found modern China, and whose recurrent political campaigns and purges were responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of his compatriots. At the north end of the square, the former leader’s giant portrait still hangs above the Gate of Heavenly Peace, the entrance to the Forbidden City. His face adorns every banknote. Mao is more than a revered dead emperor, however. In recent months, his legacy and image have become powerful weapons in the hands of the political elite as they jockey for position in the run-up to October 2012, when most senior Communist party officials will be replaced by a new generation of leaders. This year, as the party prepares to celebrate the 90th anniversary of its founding on July 1, ideological battle lines are being drawn as factions fight to gain influence and to determine the direction taken by the party. Foreign diplomats and business leaders are watching these conflicts closely for signs of whether China is heading for a dilution or even a full reversal of the market reforms that have made it an economic powerhouse. POTENTIAL POLITBURO 下一届的政治局 Politicians in the running for the next politburo standing committee (nine seats, could be reduced to seven): Bo Xilai -- Party secretary of Chongqing municipality Dai Bingguo -- State councillor Li Keqiang -- First-ranked vice-premier Li Yuanchao -- Chairman of party organisation department Liu Yandong -- First-ranked state councillor Wang Gang -- Vice-chairman, People’s Political Consultative Conference Wang Qishan -- Vice-premier Wang Yang -- Party secretary of Guangdong province Xi Jinping -- Vice-president Yu Zhengsheng -- Party secretary of Shanghai Zhang Dejiang -- Vice-premier Bo Xilai, one of the contenders for a seat on the nine-member politburo standing committee, the apex of political power, was the first to revive Mao’s ghost. In the western municipality of Chongqing, which he heads as party secretary, Mr Bo rules with an arsenal of Maoist slogans and propaganda techniques. On special occasions, residents receive “red texts” – Mao quotations sent to mobile phones. The local state television station has replaced all commercials with “red programmes” – soap operas narrating revolutionary history. Civil servants, state company staff and students are called in for the organised singing of “red songs” – hymns glorifying the country’s founding father and the party. “The sun is red, Chairman Mao is dear,” according to one. As Mr Bo has combined this campaign with a handful of highly popular policies – more polite, less corrupt police officers; more trees in the city; more affordable housing – residents rarely complain. “One should not take the ‘red’ stuff too seriously – it doesn’t affect our lives much,” says Isabelle Luo, a 26-year-old local designer. But people like Ms Luo are not, in fact, Mr Bo’s intended audience. When the 61-year-old politician peppers his speeches with Mao references, he is addressing fellow Communist party leaders – or at least some of them. Bo Xilai is the son of the late Bo Yibo, one of the party’s most senior revolutionary veterans. That puts him among the country’s influential “princelings” – along with Xi Jinping, an heir apparent for the top job. Mr Xi, vice-president and son of Xi Zhongxun, a one-time head of the party’s powerful propaganda department, is all but sure to take over from Hu Jintao as party general secretary and state president at next year’s party congress. While the appointments to the two most senior positions, president and premier, are already largely settled, with vice-premier Li Keqiang marked for the premiership, the seven remaining spots on the standing committee are still up for grabs. They have become the focus of furious politicking among the contenders. “The references to Mao Zedong are nothing more than a code for those who claim ownership over the roots of the party,” says Xiao Jiansheng, a historian and editor at a state newspaper in Hunan, Mao’s ancestral province. CONFUCIAN CONFUSION 孔儒塑像引起的混乱 Political pointers in the mystery of the moving statue. Political battles in China are almost always conducted behind closed doors but in recent months the public has been treated to fascinating glimpses of the factional struggles raging behind the walls of the Zhongnanhai leadership compound in Beijing, writes Jamil Anderlini. Since ancient times, Chinese politicians have relied heavily on symbolism and historical allegory to attack their rivals. Indeed, Mao Zedong’s opening salvo in what would become the devastating cultural revolution of 1966-76 was an arcane literary discussion of a historical drama that Mao’s acolytes alleged was an oblique attack on the chairman himself. So when a 9.5m tall, 17-tonne statue of Confucius, the ancient Chinese sage, appeared in front of the newly renovated National Museum on the north-east corner of Tiananmen Square in January, the political class took notice. One of Mao’s most destructive campaigns during the cultural revolution was launched against the “Four Olds” (old customs, old culture, old habits and old ideas) and, as the embodiment of all of these, Confucius was the prime target for the violent Red Guards. Confucius has enjoyed a revival over the last few decades and the government has funded Confucius institutes in more than 90 countries to teach the Chinese language and culture and promote the Communist party’s “soft power” abroad. But a giant bronze statue of him facing Mao’s portrait just across the road was regarded by political conservatives as a provocation. Then, one late April night, the statue mysteriously disappeared from its plinth, in what many saw as a sign of the ascendance of conservative Mao revivalists. The museum said the statue was shifted to an inner garden of its complex but refused to give a reason for its removal from the square. The move was greeted with joy by pro-Mao websites and online chatrooms. “The statue of the slave-owning sorcerer Confucius has been driven from Tiananmen Square!” cheered one Mao fan. But some commentators were a little more irreverent. “Maybe Confucius has been taken away by police for suspected economic crimes?” wrote one microblogger, in an apparent reference to the current detention of Ai Weiwei, the artist and activist accused of unspecified activities of that type. Reform advocates are hitting back. A professor who blogs under the pseudonym Diedie Bu Xiu suggests, as an alternative to Mr Bo’s “dangerous campaign”, a “Zhejiang model” – a development path modelled on the province with the most developed private enterprise sector. He predicts that this will lead to the rise of civil society and democracy. Mr Xi has signalled that he has got the message. On a widely noticed visit to Chongqing in December, he said Mr Bo’s methods “have gone deeply into the people’s hearts and are worthy of praise”. Willy Lam, a veteran China watcher, observed in a recent note for the Jamestown Foundation, the US think-tank: “Xi’s bonding with [Mr Bo] shows that the vice-president may be putting together his own team [of political allies].” Another representative of the princeling faction is making waves with references to the chairman. General Liu Yuan, son of Liu Shaoqi, one of Mao’s earliest comrades-in-arms, made an arcane but provocative call in the preface to a book by a conservative author for a return to “New Democracy”. A concept slightly more liberal than hardcore communism, New Democracy was propagated by Mao and Gen Liu’s father before the party took power, though it was later abandoned by Mao. Gen Liu’s enigmatic essay also calls for a strengthening of the military over the cultural in China, praising war as the foundation of nation-building, and expressing admiration for the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. Gen Liu, political commissar of the logistics department of the People’s Liberation Army, is expected to be appointed to the Central Military Commission, the body that ultimately controls the armed forces. For men such as Mr Bo and Gen Liu to back up their claim to power with references to Mao appears deeply cynical. Since the late chairman persecuted almost every one of his former allies, most princeling politicians – including Messrs Bo, Liu and Xi – watched their parents suffer under the ideology they now invoke. Observers therefore believe their appropriation of it is more about style than substance – an attempt to tap into a sense of nostalgia by resurrecting the trappings of Maoism without reviving any of the disastrous policies associated with it. “There is a certain renaissance of the Mao cult, but that’s among young people who have not experienced the horrors of that era,” says Mr Xiao in Hunan. Officials at the local government of Shaoshan, Mao’s ancestral home town, say there has been a steep rise in visits from tourists, including many young worshippers bearing incense. But as far as politicians are concerned, Mr Xiao adds, “they seek the most powerful symbol of the party, and Mao is the only thing that stands for that”. He argues that members of the princeling faction take a dynastic view of political power, caring about ideology only to the extent it can help them gain and maintain control. ---- Debates triggered by the Maoist revival resonate far more broadly, however. Some conservative groups, long unhappy with the naked capitalism produced by more than 30 years of economic reforms, have taken up the “Chongqing model”. “These red songs, soaked with the bright red blood of revolutionary martyrs, are the spiritual medicine people need to free themselves of the poison of western class society and spiritual opium,” according to a recent essay by Ning Yunhua, a writer on Utopia, the Maoist camp’s main website. Prominent academics have raised the stakes in the debate. Mao Yushi, an economist (no relation to Mao Zedong), demanded in an essay last month that the former leader be demoted from the status of deity and “returned to human form”. His call for an end to hagiography and the revived personality cult drove Maoists into a rage. On Utopia and other conservative forums, Mr Mao is being called a “capitalist running dog”. He is subject to taunts of “cow ghost” and “snake spirit”, terms used during the darkest days of the cultural revolution to humiliate and demonise people who often ended up tortured or beaten to death. One group has collected 10,000 signatures to support its demand that police go after the economist for alleged subversion and libel. These bitter public feuds reflect splits at the very top of the party, with factions embracing or repudiating Mao to advance their own agendas. Persistent rumours are circulating in Beijing that more liberal members of the senior leadership have suggested dropping all references to “Mao Zedong thought” in future official documents, a highly symbolic move that would break with decades of tradition. The ideological battles have even spilled out into the tightly controlled official media. In the past month, People’s Daily, the Communist party mouthpiece used to keep cadres up to date about the correct line, stunned the public by running a series of five editorials that appeared to call for political reforms. Just as officials were lecturing foreign diplomats and journalists that jailed artist Ai Weiwei was a troublemaker undeserving of their attention, one article warned of the need for greater tolerance of dissent. The final piece in the series said China would achieve stability only by allowing people to make their voices heard rather than suppressing them. According to a senior editor at a state newspaper, the series was an initiative of editorial staff with tacit backing from above. But the backlash came almost immediately. Last week, a further editorial in the People’s Daily called for political discipline and criticised some cadres for “irresponsible” comments on ideology. ----- Beyond the battle for power at the top, the struggle over Mao’s legacy has come to symbolise a more fundamental ideological split – a divide between those in the leadership who advocate moving towards a more liberal, participatory political system and a more hardline group that rejects anything to do with western-style democracy. Representing the more liberal faction is premier Wen Jiabao, whose frequent enigmatic references to the need for greater democracy and tolerance have been taken by some as support for substantive political reform. Although some analysts believe Mr Wen enjoys some support from President Hu, for now the factions arguing against such liberalisation are clearly in the ascendant. “China is at a crossroads,” says Wan Jun, a university lecturer and online commentator. “The fierce clash of ideas exposes the crisis facing socialism with Chinese characteristics.” That is a direct stab at the reforms of Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s successor, who tried to undo a large portion of the dictator’s work. For more than 30 years, Mr Deng’s model worked. Increasingly market-oriented economic reforms allowed people to grow much richer, and kept them mostly satisfied with the lack of political reform. In light of the global financial crisis and the damage wrought on the credibility of western elites, some Chinese leaders claim their country’s development model represents a rival set of values. But internally, many of those involved in the party’s ideological quarrels agree that the dividends of Mr Deng’s model are running out. They cite increasing corruption, social unrest and income inequality; as well as serious economic imbalances, an unsustainable growth model and an erosion of the party’s authority. It is this daunting list of problems that will confront those of today’s aspirants who manage to secure a position in the new leadership. The ghost of Mao can help Mr Bo and his fellow contenders only so much. Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2011. | |

No comments:

Post a Comment