Recession with Chinese Characteristics 中国特色的经济衰退

Continued growth or collapse? The only certainty is more repression.

By John Derbyshire

When, 30 years ago, Deng Xiaoping authorized a retreat from the Maoist command economy, he called his plan “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” After a spell of cautious experimentation, Deng’s schema blossomed into the export-led, double-digit-growth Chinese economy we have become familiar with this past couple of decades. Now, with the deepening worldwide recession, China watchers are puzzling over the effect of the crisis on China and the ability of China’s government to ride out the storm.

As usual with China, opinion — even informed opinion — is all over the place. At one end are those predicting political collapse. One scholar known to me, who keeps anonymity to protect his China access — a common attitude; no one has forgotten the example of Steven Mosher — says that China’s 2008-Q4 and 2009-Q1 figures for electricity production look dire, and that widespread rumors say the leadership is leaning on the country’s wealthiest industrialists to buy Chinese government paper, so the government in turn can continue to buy U.S. government paper. (I have heard the same rumor about Russia.)

For the contrary view, business writer Robert Peston at the BBC, reporting on Prime Minister Wen Jiabao’s address to China’s National People’s Congress last week, tells us that:

The Chinese economy remains . . . exceptionally strong. It’s true . . . that growth in China has been slowing down — and regions particularly dependent on exports, especially the south, have suffered mass closures of factories and painful rises in unemployment. But many economists believe that the Chinese economy is still growing . . . Thus Stephen Green at Standard Chartered reckons there was 1 percent growth between the third and fourth quarters of last year, and that there’ll be a similar expansion in the first three months of this year. For 2009 as a whole, he’s forecasting GDP growth of between 6 and 7 percent . . . That may be a long way from the low teens growth of last year. But it looks pretty amazing compared with the very painful recessions in Japan, the UK, Germany and the US.

Well-informed observers have been forecasting a Chinese collapse for at least a decade to my certain knowledge. That doesn’t mean it won’t happen, but it suggests caution when reading the more pessimistic forecasts. China is a very murky place, and anything that happens there will likely take us by surprise. The only thing that can be said for sure about the near future is that this will, for China, be a recession with Chinese characteristics. As Peston reports, Chinese government action so far has been along the same lines as our own — tax cuts, more public spending and borrowing, bailouts for key industries, more financial regulation — only on a smaller scale. Stimulus-wise, the Obama administration is well to the left of the Chinese Communist party.

This much can at least be depended on: In an economic slowdown, the Communist party will be even more determined to root out “enemies of the people.” Not that the post-Deng leadership has ever shown any inclination toward political reform; against its own citizens — those who dare to present even the smallest, most deferential challenge to party authority — the Communist leadership maintains rigid Leninist norms. The pledges of human-rights improvements given ahead of the Peking Olympics last year were never sincere, and were tossed contemptuously into the shredder even before the opening ceremony, as the Washington Post made clear in its report on dissident Ji Sizun the other day:

When Ji Sizun heard that the Chinese government had agreed to create three special zones in Beijing for peaceful public protests during the 2008 Summer Olympics, he celebrated. He said in an interview at the time that he believed the offer was sincere and represented the beginning of a new era for human rights in China . . . It is now clear that his hope was misplaced . . . China never approved a single protest application — despite its repeated pledges to improve its human rights record when it won the bid to host the Games. Some would-be applicants were taken away by force by security officials and held in hotels to prevent them from filing the paperwork . . . In January, [Ji] was sentenced to three years in prison.

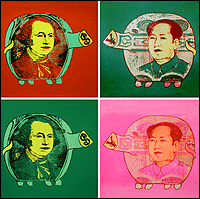

The other arm of the Communist regime’s survival strategy consists of appeals to nationalism via angry defiance of foreign “provocation.” In the absence of any actual provocations, something can easily be staged. That was the motive behind the weekend fracas in the South China Sea. The Communists have to carry out a tricky balancing act here. On the one hand, they know that they need to cooperate with the U.S. if they are ever to get back to those double-digit growth rates. (As the blogger Fabius Maximus wittily observes, in 50 years we have gone from Mao Tse-tung’s assertion that “Only socialism can save China!” to the present assumption that “Only China can save capitalism!”) On the other hand, fingers periodically need to be poked in the foreign devils’ eyes to appease China’s huge cohort of rabidly nationalistic young men. This is more necessary right now than ever.

For one thing, the number of college graduates in China has been increasing very rapidly: 650,000 more graduated last year than the year before. When there were few graduates in a fast-growing economy, educated youngsters could pick and choose. Now there are many graduates in a comparatively sluggish economy, and the prospects fall short of their expectations. For another thing, this year is the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square killings that so horrified the civilized world. It is also the 90th anniversary of the May Fourth movement, an epochal event, also student-led, that transformed the culture and mental outlook of educated Chinese, among them the 25-year-old Mao Tse-tung.

And then, Tibet. March 10 was the 50th anniversary of the great uprising against Chinese occupation that led to the flight of the Dalai Lama. Fifty years have done nothing to reconcile Tibetans to their subjection, and the Communists show every sign of knowing this. The Tibet Autonomous Region has been under tight lockdown for weeks, along with Tibetan territories in neighboring “Chinese” provinces. To add insult to repression, the Communists have declared March 28th to be “Serfs’ Emancipation Day,” in line with their propaganda about having liberated Tibetans from “feudalism.” Perhaps the massive Chinese military and police presence in Tibet is there to prevent the Tibetans from breaking into excessively joyful spontaneous demonstrations of gratitude to their liberators.

The Chinese Communists’ treatment of Tibet could go into political-science textbooks as history’s most outstanding example of unimaginative statecraft. The utter absence of imagination among the national leadership is in fact the strongest reason to fear for China’s stability. The last 20 years of fast-rising prosperity have been rather easily accomplished. The leadership had to do little more than relax some Maoist absurdities and stand back while stuff happened. The years to come will present much greater challenges, calling for imaginative handling. There was no hint of any capacity for that in the robotic, insomnia-cure addresses to the National People’s Congress last week.

It is now a hundred years since Sun Yat-sen formulated the Three People’s Principles as a framework for modern China. They were: harmonious nationhood, consensual democracy, and a sound economy. Military patrols in the streets of Lhasa testify to failure in the first of the Three Principles; the brutish silencing of harmless dissidents like Ji Sizun makes a mockery of the second. Thirty years of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” has at least delivered some progress on the third. If that progress falters, the past century of Chinese history might as well not have happened.

— John Derbyshire is an NRO columnist and author, most recently, of Unknown Quantity: A Real and Imaginary History of Algebra.

No comments:

Post a Comment