Vaclav Havel - Former Czech Republic President

Ronald Reagan - Former American President

哈维尔 - 一个深知自由价值的英雄 Havel - A Hero the World Needs the Most

每日一语:

作为每一个曾生活在专制下的人,他一定要反省与忏悔他自身曾对专制的沉默,纵容,协助与容忍。 如果他想真正地赢得自由,他一定要从道德的虚无与混乱中自拔出来走入道德清晰的生活。 --- 陈凯

Having lived through despotism and tyranny, a person has to reflect on his own silence, acquiescence, assistance and tolerance of the evil regime of which he is inescapably a part. He has to repent in order to progress. He has to pull himself out of the morass of moral nihilism and moral confusion in order to win freedom for himself. --- Kai Chen

------------------------------------------------------------

Dear Visitors:

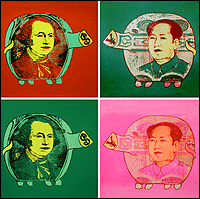

Yesterday my wife and I visited Ronald Reagan Library in Simi Valley. Throughout the visit I couldn't help feeling deeply moved by a great spirit of optimism and a bright outlook toward the future by our former president.

Reagan had been living in America all his life and not been subjected to tyranny, but he understood the value of freedom. I have to attribute that understanding to his deep faith in God. Because of that deep faith, Ronald Reagan was never morally confused or shaky about what America stood for. This is much more than I can say today about many who live in America, some of whom are in high positions of American government. They have lost that essential spirit of freedom and optimism toward future. They even want to change what America is about to suit others' appetite and liking, as though there were no God, as though there were only others' pleasure toward which America has to cater.

America is great precisely because America is the only country in the world professed to be UNDER GOD, never under men. America is great precisely because American people are armed with guns and the Bible. America is great precisely because America is consisted of many who understand the horror, the misery and evil of tyranny, who treasure paying a necessary price for that invaluable universal goal -- Freedom.

Havel is such a hero who had lived through tyranny and understood the value of freedom. He, along with Ronald Reagan, is my hero. I now paste this article about Havel below for you to read and enjoy.

Have faith in God and treasure Freedom forever. Kai Chen

-------------------------------------------------------------

哈维尔 - 一个深知自由价值的英雄 Havel - A Hero the World Needs the Most

Why We Need More Leaders Like Vaclav Havel

The courageous playwright who destroyed Communism in Czechoslovakia could teach us much about the need to defend Western freedoms against totalitarian Islam.

June 6, 2008 - by Bruce Bawer

No one could have blamed Havel, in the flush of victory, for feeling less than charitable toward the Communists. But he refused to wreak vengeance, rejected calls to outlaw the Communist Party, and strove to transcend old hatreds; he asked that all Czechs and Slovaks work together to repair the damage Communism had caused — damage to everything from the nation’s infrastructure to its very soul — and to build a new, free society of which everyone could be proud. In “Power and the Powerless” he had imagined the modern world surpassing not only totalitarianism but also Western democracy in its present form and attaining a “post-democracy” even more fully dedicated to individual liberty; in reality, it became difficult enough to take the wreck that was post-Communist Czechoslovakia — a country whose economy was a basket case, whose rivers were sewers, and whose people had been rendered ill-equipped by decades of fear and oppression to make the most of living in freedom — and turn it into a modern democracy with a functioning market economy. Yet Havel and others, to their everlasting credit, managed within a reasonably short time to achieve just this.

In his first New Year’s address to Czechoslovakia, Havel noted that during the Communist era the country’s leaders had filled their New Year’s addresses with glowing words about “how our country was flourishing, how many million tons of steel we produced, how happy we all were.” Havel noted that in fact Czechoslovakia’s economy was a joke (”Entire branches of industry are producing goods that are of no interest to anyone”), that it had “the most contaminated environment in Europe” (at the time, the country’s name was synonymous in many people’s minds with waterways polluted beyond belief), and that, worst of all,

we live in a contaminated moral environment. We fell morally ill because we became used to saying something different from what we thought. … We had all become used to the totalitarian system and accepted it as an unchangeable fact and thus helped to perpetuate it. … None of us is just its victim. We are all also its co-creators.

Yes, co-creators. It was necessary, he insisted, that Czechs and Slovaks refuse to see themselves as victims — for only thus would they realize it was up to them to change their lot. It would do no good to spend their time blaming their former Communist masters for their troubles.

In 1993, Czechoslovakia split peacefully into two countries, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, with Havel becoming president of the latter. He stepped down in 2003, but continued to fight oppression. (He was admirably outspoken, for example, in his criticism of Fidel Castro, whom many other European leaders adored.) He has also talked about Communism’s psychic legacy, which, though in the main profoundly negative, as it stunted its subjects both morally and spiritually, also had a positive side: for it taught people like him to cherish the freedom they didn’t have. And after they had won it, they knew they must never take it for granted. To stand up for freedom — not only theirs but that of others — was for them a profoundly felt moral obligation. It was worth their vigilance, their sacrifice. In the West, Havel knew, this kind of awareness and commitment were largely absent: “Naturally, all of us continue to pay lip service to democracy, human rights, the order of nature, and responsibility for the world,” he wrote, “but apparently only insofar as it does not require any sacrifice.” The West, he worried, had “lost its ability to sacrifice” — a point also made by Russian dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn in a 1978 commencement address at Harvard. “A decline in courage,” Solzhenitsyn told the graduates on that day three decades ago,

may be the most striking feature which an outside observer notices in the West in our days. … Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling groups and the intellectual elite, causing an impression of loss of courage by the entire society. Of course, there are many courageous individuals, but they have no determining influence on public life.

When one examines the responses of many in the West to the challenge of Islam, it’s hard not to feel that Havel and Solzhenitsyn were absolutely right. Living a lie, once ubiquitous behind the Iron Curtain, is now widespread in the West owing to a profound fear of Islam. Every Western journalist who writes that Islam is a religion of peace, who chides terrorists for hijacking a peaceful religion, and who celebrates Muhammed as a messenger of ecumenical harmony — all the time knowing that these are lies — is doing the equivalent of the greengrocer putting a sign in his window to avoid trouble. For most of us in the West today, life is extraordinarily easy compared with life in a dictatorship — and it’s precisely for this reason that jihadists are making inroads upon our freedoms with so little effort. “The only genuine values,” Havel has written, “are those for which one is capable, if necessary, of sacrificing something.” By this measure, how many people in the West today are truly dedicated to liberty? Today, in the Western world, if a group of Muslims starts bullying non-Muslims and seeking to limit their freedoms, most of the latter will not raise a peep in protest — instead, they’ll criticize those who resist. For those accustomed to the comfort of life in the West — a life that’s free of the perils of totalitarian societies and that rarely requires courage — standing up to bullies doesn’t come naturally. It’s scary to confront jihadist gangsters, and far easier to join the mob of people shaking their fingers at the few who dare to confront them. It’s also easy — and self-flattering, and immoral, and irresponsible — to pretend that you’re living in a totalitarian society when in fact you’re free. Those who say that America has become a totalitarian state either don’t have the slightest understanding of totalitarianism or are cowards playing at being heroes.

A dissident hero under Communism, Havel became in the post-Cold War world an international symbol of the triumph of individual conscience over the forces of tyranny. He traveled the world, won prizes, addressed a joint session of the U.S. Congress. Meanwhile, back home in Prague, he suffered the fate of all politicians. Though in his first years as president he was almost universally admired, even revered, over the years he was increasingly criticized on a variety of fronts. He was attacked both for being too informal and for putting on airs; for being too conciliatory with the Communist ex-rulers and for being too hard on them; for being too enthusiastic about the free market and too hostile to it. As a dissident, Havel had stood for principle; as a politician he was obliged to make compromises. Keane, who writes respectfully about Havel the dissident, snipes tirelessly at Havel the post-revolution politician, apparently cataloging every last gripe that anybody in Czechoslovakia might have had about him. Keane even goes so far as to describe Havel’s life as a tragedy — the noble crusader who bested the powers of evil ending up just another politician at a desk. This interpretation, however, is obscene; it smacks of Communist-style utopianism. For a person living under totalitarian terror, the greatest dream is simply to be able to lead a normal life. Havel’s triumph is that he and his countrymen liberated themselves into a world in which they were no longer forced to live in terror, a world in which they didn’t put their lives on the line with every action they took and every word they spoke. Havel himself considers his life story inspiring, as well he should — for it shows, as he has said,

that an apparently hopeless cause can have a happy ending. That story may seem somewhat like a fairy tale, somewhat kitschy; you can laugh at it, but at the same time it wouldn’t be entirely right to laugh at it. It’s good when people admire such an outcome. It speaks well of their understanding of values.

Indeed. The person who can’t be moved by Havel’s triumph has no appreciation for his own freedom and can’t imagine what it would mean to lose it.

How familiar are people in the West with Havel and his accomplishments? When he arrived at Columbia University in late 2006 to spend a few weeks on campus delivering lectures and taking part in panel discussions, few of the undergraduates could have picked him out in a lineup. Gregory Mosher, director of the university’s Arts Initiative program, admitted to the New York Times, “They had no idea who he is. … [They] thought he was a hockey player.” Yet is it possible that any of these Ivy Leaguers — supposedly among the best and brightest of their generation — had not heard of those fabled First Amendment heroines, the Dixie Chicks? How many of them not only knew the name of Che Guevara, that bloodthirsty Stalinist, but also thought he was cool (and had t-shirts to prove it)? When Mahmoud Ahmadinejad showed up a year later to give his address at Columbia, was there a single undergraduate on Morningside Heights who didn’t know who he was? In a time when freedom in the West is seriously threatened by Islamism and its Western allies and appeasers, it’s imperative that young people cherish their freedom, that they sincerely honor the memory of the men and women who fought and died for it, that they recognize the forces in the world today that threaten it, and that they be prepared to make an effort — and, yes, even make sacrifices — to preserve that freedom for future generations. In order for them to be able to do this, it is vital that they have before them the rare and remarkable example of individuals such as Vaclav Havel.

No comments:

Post a Comment