China's "Princelings" Economy 中国的太子党经济

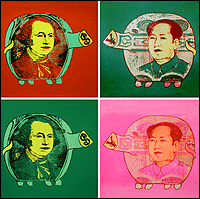

陈凯博客: www.kaichenblog.blogspot.com 中国的新富无一不是党朝公子/女 All the Chinese Newly Rich are Princelings (Source from an Unknown Emailer:) 胡海峰:威視公司總裁,公司市值 838億元 溫雲松:北京優創科技有限公司總裁,公司市值 433億元 江綿恆:中國網通創辦人,公司市值 1,666億元 朱燕來:中銀香港發展規劃部總經理,公司市值 1,644億元; 李小鵬:華能電力董事長,公司市值 176億元 (陕西省副省长) 李小琳:中國電力副董事長,公司市值 82億元 榮智健:中信泰富主席,公司市值 476億元 王軍:中國中信集團董事長,公司市值 7,014億元 王京京:中科環保副主席,公司市值 7.7億元 孔丹:中信國際金融董事長,公司市值 99億元。 但你知道嗎? 胡海峰是胡錦濤之子 溫雲松是溫家寶之子 江綿恆是江澤民之子 朱燕來是朱鎔基之女 李小鵬是李鵬之子 李小琳是李鵬之女 榮智健是榮毅仁之子 王軍是王震之子 王京京是王軍之子,王震之孫 孔丹是孔原/許明之子 (孔原是中央調查部部長、總參顧問等職;母親則是國務院副秘書長) 而這個你又有聽聞嗎? 據一份大陸研究報告披露,大陸的億萬富豪中,九成以上都來自高幹子女。其中 2,900多名高幹子女合共擁有資產二萬多億人民幣。 他/她們雖然是高幹子女,但是本著“為人民服務”的精神,絕對不會借家庭背景來謀私奪利! 你有懷疑嗎? 借用前中國鐵道部發言人王勇平的金句:“不管你們信不信,反正我信了!” ----------------------------------------------------- China's new rulers Princelings and the goon state 中国的“公子党”与流氓政体  The rise and rise of the princelings, the country’s revolutionary aristocracy Apr 14th 2011 | BEIJING “THERE are some sour and smelly literati these days who are utterly abominable,” a retired military officer reportedly told a recent gathering in Beijing. “They attack Chairman Mao and practise de-Maoification. We must fight to repel this reactionary counter-current.” At the time, two months ago, the colonel’s crusty words might have had the whiff of a bygone era. Today, amid a heavy crackdown on dissent, they sound cruelly prescient. One of the most prominent literati, Ai Weiwei, is among dozens of activists the security forces have rounded up recently. Mr Ai, an artist who is famous abroad, was detained in Beijing as he attempted to board a flight to Hong Kong on April 3rd. There has been no official confirmation since of his whereabouts. Officials say that he is being investigated for unspecified economic crimes, but the Global Times, a Beijing newspaper, warned that Mr Ai had been skirting close to the “red line” of the law with his “maverick” behaviour. In other words, he had apparently provoked the Communist Party once too often. Since the late 1970s, when China began to turn its back on Maoist totalitarianism, the country has gone through several cycles of relative tolerance of dissent, followed by periods of repression. But the latest backlash, which was first felt late last year and intensified in late February, has raised eyebrows. It has involved more systematic police harassment of foreign journalists than at any time since the early 1990s. More ominously, activists such as Mr Ai have often simply disappeared rather than being formally arrested. It is an abnormally heavy-handed approach, one unprompted by any mass disturbances (recent anonymous calls on the internet for a Chinese “jasmine revolution” hardly count). This suggests that shifting forces within the Chinese leadership could well be playing a part. China is entering a period of heightened political uncertainty as it prepares for changes in many top positions in the Communist Party, government and army, beginning late next year. This is the first transfer of power after a decade of rapid social change. Within the state, new interest groups have emerged. These are now struggling to set the agenda for China’s new rulers. Particularly conspicuous are the “princelings”. The term refers to the offspring of China’s revolutionary founders and other high-ranking officials. Vice-President Xi Jinping, who looks set to take over as party chief next year and president in 2013, is one of them. Little is known about his policy preferences. Some princelings have been big beneficiaries of China’s economic reforms, using their political connections and Western education to build lucrative business careers. Other princelings are critical of China’s Dickensian capitalism and call for a return to socialist rectitude. Some straddle both camps. Prominent princelings in business include President Hu Jintao’s son, Hu Haifeng, who headed a big provider of airport scanners; and Wen Yunsong, a financier who is the son of Wen Jiabao, the prime minister. Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, argues that a shared need to protect their interests binds these princelings together, especially at a time of growing public resentment against nepotism. Since a Politburo reshuffle in 2007, princelings have occupied seven out of 25 seats, up from three in 2002. The Mao-loving ex-colonel was talking to a group called the Beijing Friendship Association of the Sons and Daughters of Yan’an (where Mao Zedong was based before his takeover of China in 1949). No prizes for guessing that the group favours socialist rectitude. Its president is Hu Muying, a daughter of Mao’s secretary, Hu Qiaomu. Mr Hu was a Politburo hardliner in the 1980s who died in 1992. Other princelings are association members, though it is unclear how many are current or expected holders of high office. In her speech to the gathering Ms Hu said she rejected the word “princelings”, but declared: “We are the red descendants, the descendants of the revolution. So we have no choice but to be concerned about the fate of our party, state and people. We cannot turn our backs on the crisis the party faces.” The crisis, as her sort see it, is rampant corruption, a widening gap between rich and poor, and a collapse of faith in communist ideology. Details of Ms Hu’s speech and the former colonel’s were posted on several websites controlled by China’s remaining Maoist hardliners. Journals put out by the hardliners were forced to close a decade ago because they were too blunt in their criticism of China’s economic reforms. Yet the websites have kept up their tirades, including fierce denunciations of Ai Weiwei and other liberal intellectuals long before the recent arrests. The Maoists’ lingering influence has been evident for the past couple of years in the south-western (and Scotland-sized) municipality of Chongqing. There, one of the country’s most powerful princelings, Bo Xilai, Chongqing’s party secretary, has been waging a remarkable campaign to revive Maoist culture. It includes getting people to sing Mao-era “red songs” and sending text messages with reams of Mao quotations. A local television channel has even started airing “revolutionary programming” at prime time. Last year Chongqing’s fawning media ascribed a woman’s recovery from severe depression to her singing Mao-vintage songs. The campaign has drawn plenty of attention. Mr Bo is a Politburo member who is thought to be a strong contender for elevation next year to its standing committee, the party’s supreme body. He has become a darling of the Maoists (their websites say that the same colonel singled out Mr Bo for praise, to applause from the audience). For a long time it had been thought that Mr Bo and Mr Xi did not get on. But in December Mr Xi visited Chongqing and said its red revival had “deeply entered people’s hearts”. It deserved all its praise. Few people—certainly not Mr Bo or other contenders for power—are calling for a return to Maoist despotism and an end to market economics. What worries many liberals, however, is that they share Mao’s high-handed approach to the law. In Chongqing a sweeping campaign against the city’s mafia-like gangs and their official protectors has won Mr Bo many plaudits in the state-controlled press. But the jailing of a defence lawyer for one of the mobsters, for allegedly trying to persuade the accused to give false testimony, has led many to worry that Chongqing’s courts will do anything to prevent lawyers from challenging the prosecution. He Weifang, a prominent legal expert at Peking University, wrote this week that recent events in Chongqing “threatened the basic principles of a society under the rule of law”. The manner of the recent crackdown could be a sign that Mr Bo’s approach (which includes dollops of spending on housing for the poor) is gaining favour in Beijing. It is also a sign of the increased influence of the domestic security apparatus since 2008, when China pulled out all the stops to stop unrest marring the Olympic games in Beijing. The power of Zhou Yongkang, the member of the Politburo’s standing committee in charge of security, is widely thought to have grown along with a rapid increase in government spending on his portfolio. More liberal thinking has not been entirely suppressed. The party chief of Guangdong province in the south, Wang Yang, who is another (non-princeling) contender for the Politburo’s standing committee, is widely seen as a bit more open-minded. Shenzhen, a special economic zone in Guangdong, has been experimenting in giving a freer rein to NGOs. The province’s newspapers are among the country’s most spirited (for which they are bitterly attacked by leftist websites). But Mr Wang has a cautious streak, too. The official media reported this week that 80,000 “potentially unstable people” had been evicted from Shenzhen in preparation for a sporting event this summer. One of the most powerful criticisms of the clampdown came on April 8th from Mao Yushi, a notable economist. In a blog posting at Caixin Media, an outspoken publishing group, Mr Mao accused leaders of making a mistake by neglecting political reform in their plans for China’s development in the next five years. Spending ever greater sums on maintaining stability, he said, just made citizens more hostile. Determined not to allow any disruption to next year’s high politics, Chinese leaders are willing to take that risk. |

No comments:

Post a Comment