BEIJING — Two years ago, one of China's most successful investment bankers broke away from his meetings in Berlin to explore a special exhibit that had caught his eye: "Hitler and the Germans: Nation and Crime." In the basement of the German History Museum, He Di watched crowds uneasily coming to terms with how their ancestors had embraced the Nazi promise of "advancement, prosperity and the reinstatement of former national grandeur," as the curators wrote in their introduction to the exhibit. He, vice-chairman of investment banking at the Swiss firm UBS, found the exhibition so enthralling, and so disturbing for the parallels he saw with back home, that he spent three days absorbing everything on Nazi history that he could find.

"I saw exactly how Hitler combined populism and nationalism to support Nazism," He told me in an interview in Beijing. "That's why the neighboring countries worry about China's situation. All these things we also worry about." On returning to China he sharpened the mission statement at the think tank he founded in 2007 and redoubled its ideological crusade.

He's

Boyuan Foundation exists almost entirely under the radar, but is probably the most ambitious, radical, and consequential think tank in China. After helping bring the Chinese economy into the arena of global capital through his work at UBS, He now aspires to enable Chinese people to live in a world of what he and his ideological allies call "universal values": liberty, democracy, and free markets. While the foundation advises government institutions, including leaders at the banking and financial regulators, its core mission is to "achieve a societal consensus" around the universal values that it believes underpin a modern economic, political and social system.

"This is the transition from a traditional to a modern society," He says.

The challenge for Boyuan is that "universal values" clash with the ideology of the Communist Party, which holds itself above those values. "Boyuan is like the salons that initiated and incubated the governing ideas of the French revolution," says David Kelly, research director at a Beijing advisory group who has been mapping China's intellectual landscape. "They explicitly want to bring the liberal enlightenment to China."

The 65-year-old He is at the forefront of an ideological war that is playing out in the background of this week's epic leadership transition, where current Chinese President Hu Jintao officially yielded power to Xi Jinping. At one pole of this contest of ideas are He's universal values; at the other, the revolutionary ideology of the party's patriarch, Mao Zedong. This battle for China's future plays into the decade-long factional struggle between Hu and his

recently resurgent predecessor, Jiang Zemin.

Jiang's ideological disposition has evolved in chameleon fashion but in recent years he has hinted that if the party remains inflexibly

beholdento Mao Zedong-era thought and Soviet-era institutions then it faces a risk of Soviet-style collapse.

When He Di stepped down as chairman of UBS China in 2008 -- after leading the investment banking capital raising

charts for four straight years

-- UBS gave him an office, a secretary, and a salary with no minimum work requirements. He continued to find UBS lucrative deals, capable princelings to hire (such as the son of former Vice Premier Li Ruihuan) and introductions to wealthy private banking clients. The Swiss bank also gave him $5 million to inject into Boyuan, just weeks before the 2008 global financial crisis, without any strings attached except the appointment of a UBS representative on his board, according to Boyuan representatives. He tipped in $1 million of his own as he redeployed his resources to build a platform for ideas.

"One day I picked up the phone and called potential board members." he said. "I called 6 or 7 ministers or vice ministers, without any hesitation."

Boyuan's Beijing headquarters is an elegantly renovated courtyard home on the north side of the city. Behind He's desk is a wall of books on history, philosophy, and reform. Over a simple lunch of braised vegetables and endless cups of tea, he told me how his commitment to liberal values is rooted in a strand of Communist Party tradition that flourished in the 1980s and has since been subordinated but not entirely vanquished. "My grandfather and father were all fighting to establish not dictatorship, not feudalism, but so that people at the grassroots could enjoy a good life." He's grandfather was a vice-minister in the Kuomingtang government that ruled China until the Communists defeated it in 1949; he was beaten to death during the Cultural Revolution.

He's father was an influential agricultural minister in the reformist 1980s, a talented agricultural

scientist respected for his integrity who helped guide China's peasants to

shed the communal owning of land. This was China's moment of enlightenment, He says, where the revolutionary veterans respected the judgment of peasants and entrepreneurs alike to choose what to plant, what to make, and how to take it to market. The trick was simply to get out of the way. "At that time, the top leaders really understand the concept of so-called ‘universal values,' which means human rights and allowing the people freedom to choose what they want," says He. "They respected the abilities of the people, reflecting a universal value not necessarily coming from the West but based on human beings basic needs."

He had originally intended the Boyuan Foundation to be a retirement pursuit, a project of collective self-enlightenment with close childhood friends. His worries grew as he watched a fellow princeling, Bo Xilai, breathe new life into the spirit of Mao and whip up a popular frenzy in Chongqing, the inland mega-city Bo governed. As he watched Chinese citizens embrace modernity and the party-state slide back toward the revolutionary ideology of his childhood, his ambitions turned from supporting China's modern evolution to saving it.

When He returned to Beijing after his visit to Berlin in late 2010,

he discovered that renowned scholars had been investigating those same parallels, even if they could not publicize their work. Shanghai historian Xu Jilin had traced China's leftward turn (leftists in China are the more conservative faction, who favor a more powerful state) to the 1999 U.S. bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia which grew into a "nationalist cyclone," a moment when China's rising pride, power, and the political phenomenon of Bo Xilai started to gain momentum. "Statist thinking is gaining ground in the mainstream ideology of officialdom, and may even be practiced on a large-scale in some regions of "singing Red songs and striking hard at crime," Xu said in a recent talk delivered to the Boyuan Foundation. "The history of Germany and Japan in the 1930s shows that if statism fulfils its potential, it will lead the entire nation into catastrophe."

Xu's antidote is right out of the

Boyuan mission statement: "What a strong state needs most is democratic institutions, a sound constitution and the rule of law to prevent power from doing evil," says Xu.

He Di believes the overwhelming majority of Chinese people are on his side. "If you test how many Chinese people really want to return to Mao's period, to become North Korea, I don't believe it's 1 percent of them" he said.

He's adversaries -- many of whom call for a return to the ideals of a Maoist era -- are skeptical of private capital, appalled by rampant corruption, and antagonistic towards what they see as dangerous Western values. These adversaries, whose heroes include the fallen political star Bo Xilai and the politically wounded corruption-fighting general Liu Yuan, have a term for everything that He Di's Boyuan represents: "

The Western Hostile Forces." Luckily, He has the chips to play in such a high-stakes game.

Besides his own princeling roots, which protect him from the state, He has the backing of his foundation's chairman Qin Xiao, who held a ministerial-level position as chairman of

one of China's top state-owned financial conglomerates. Boyuan's directors include Brent Scowcroft, the former U.S. national security advisor. The Boyuan steering committee includes the publisher of the path-breaking investigative magazine

Caijing, a son of one of the most important generals of the revolution (Chen Yi), and a group of officials who, between them, manage the largest accumulation of financial assets in the history of global capital.

He's childhood friends who have worked closely with Boyuan include the governor of the People's Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan, and Wang Qishan, the financial-system czar who is set to enter the Politburo Standing Committee, China's top decision making body, this week. They, along with several other princelings who have risen to the top of Chinese finance, became close friends, ironically, when they were

red guards, fighting "capitalist roaders" in Mao's Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s.

Many of the protagonists at Boyuan have levers of the state at their disposal, and are organizing and challenging the party line in ways that would lead ordinary citizens to be branded as dissidents. Further in the organization's background, offering moral and practical support, are members of some of China's most powerful families -- including former security chief Qiao Shi, former premier Zhu Rongji, and former president Jiang Zemin.

He traces China's spiritual and policy drift to 2003, the year in which the team of then President Jiang and Premier Zhu entrusted the party and government apparatus to their successors Hu and Wen Jiabao. He says the administration moved away from "opening and reform" -- former leader Deng Xiaoping's policy of bringing China in line with the rest of the world -- and the resulting vacuum was filled with counterproductive criticism of privatization and reform. Leaders are isolated from their mid-level officials, each bureaucracy is siloed from the next, and there is no framework to mediate their interests or debate the wider merits of any particular proposal, he says. And once they started back down the old road of central planning, high-ranking officials grew addicted to the power it brought them. "The current leaders have really disappointed because I don't know what they believe," says He. "They were educated by the party, the old doctrines of Marxism, yet

they lack growth experiences at the grassroots. They are really engineers who still want to enjoy the dividends from the previous generation leadership."

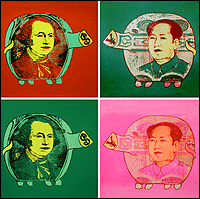

He believes in China's ability transform itself but knows it might not happen easily. He thinks Mao was an aberration who hurt his family's 100-year quest to bring China into modernity. Mao saw peasants and workers as an undifferentiated mass to be organized and mobilized, but not respected -- a man who represents China's past and used communism instead of Confucianism as his doctrine of control. "Mao called himself Qin Shihuang plus Stalin," He said, referring to China's first emperor. "He used revolution to repackage China's despotic tradition and crown himself emperor."

When Deng and his successors committed to the market they also committed to the values that underpinned it, He says, including the ideal of law. Hu, by contrast, eviscerated the integrity of the individual, and his administration's combination of extreme nationalism, extreme populism, and state capitalism means that history can repeat itself, He warns.

And that's why the Nazi exhibit scared him so.

18大前民众大规模撕毛像声援四青年。(网路图片)

18大前民众大规模撕毛像声援四青年。(网路图片) 18大前民众大规模撕毛像声援四青年。(网路图片)

18大前民众大规模撕毛像声援四青年。(网路图片)