With God in China 神与人在中国

With God in China 神与人在中国

by Theresa Marie Moreau First Published in The Remnant

Joseph Marie Louis Stanislas Winance was 4 years old when he stood on a train platform in Mons, Belgium, in 1914. Surrounded by his family, he squeezed his way past long skirts and stepped over thick leather shoes to say goodbye to his Aunt Marta Reumont, who was heading to China that June morning to become a novitiate with the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary.

“Aunt Marta, one day I will go to China and be your cook,” he said, looking up into her smiling face.

Little did that small boy realize how part of his childhood pledge would come true. For 20 years later, as a cleric in St. Andrew Abbey in Bruges, Belgium, Winance was walking along the cloister, reading his breviary when he received an order to go to the office of Father Abbot Théodore Nève.

“My dear son,” Nève said to the 24-year-old dressed in the long black Benedictine habit, draped in the long black shadows of the late afternoon, “I plan to send you to China.”

“Yes,” was all Winance said, but he wasn’t prepared for what he heard. He didn’t sleep all that night. His thoughts dwelled on the trouble the Communists had caused in Szechwan, the province where he would be sent. His Aunt Marta, who had become Sister Marie Jeanne Françoise de Chantal, mourned the loss of several buildings her order had built in the city of Suining and that the Red armies had burned and destroyed.

Nonetheless, after a restless night, the morning brought a tranquility that sedated his soul. He accepted his fate as the will of God and wrote to tell his parents about the future mission of their eldest of four sons.

Two years later, on the morning of September 4, 1936, the bells of St. Andrew rang out to celebrate the departure of three newly ordained priests: Father Vincent Martin, Father Wilfrid Weitz and Winance, who as a novitiate had taken the name Eleutherius. They were all young men in their 20s who had dedicated their lives and their work to God. They were headed for the Republic of China.

Before leaving the cloister, Winance received a bon voyage gift from Nève. “The Rule of St. Benedict,” with the following inscription: “I wish never to see you again.” Winance smiled. He completely understood the message. Many had left the abbey for their missions, but some had failed and returned. He slipped the book into his leather suitcase – a gift from his Uncle Henri Reumont, a Capuchin missionary with the religious name Father Damian.

The three priests traveled to China via Moscow, the Communist capital of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. There they boarded the Trans-Siberian Railway’s Trans-Manchurian line and readied for the 5,568-mile trip to Peking (old form of Beijing), China’s northern capital. There he paid a visit to a woman he hadn’t seen in many years.

“Here is my cook in China,” Aunt Marta joked as she introduced her lanky nephew to her sisters in the convent. She had not forgotten. It was a marvelous reunion.

From Peking, it was another train, to Hanku, a big city on the third longest river in the world – the Yangtze, also known as the Chang Jiang and the Blue River. Then west. Their steamboat coughed its way along the water, which flowed red, a prophetic color of muddied blood, and chugged between moss-covered sky-high gorges. Winance stared at the mountains that broke through the water and stretched straight up, endlessly. One of the wonders of the world, he thought.

Passing Chinese junks with their dragon-wing sails flapping, Winance’s boat pulled up for a breather in Chungking. Then one more ship, one more day, northward, to Hechuan, where Winance and his two confreres hired porters, lovers of the opium pipe who bore their burdens – priests and possessions – upon chairs dangling from poles that rode upon their calloused shoulders. Yes, the priests had traveled from West to East, from Occident to Orient, but in their journey, they had been, seemingly, transported – in all they saw, in all they experienced – from the 20th century back to the 14th.

Late one afternoon, after a week of traveling on foot and upon chair through Suining, Pengxi, Nanchung, a final deep valley led up a hill to the other side. At the top, the men paused. Winance walked to the edge and looked down. Just below, for the first time, he saw his future home: SS. Peter and Andrew Priory of Nanchung.

When they arrived at the hilltop, the day was gray. So, too, was Winance’s mood. I shall never be happy here, he thought.

It was 5:15 in the afternoon, November 19, 1936. The sun, still up, but sinking fast. Winance looked at the main building, designed with a classical Chinese style, its roof corners decorated with upturned eaves, like erect dragon tails. A courtyard peeked out from the center. To the left, a small red-sand mountain covered with rows of mandarin orange trees leaning sunward, lurching from their three hillside terraces. For the final 10 minutes of a 10-week-long journey, Winance jogged downhill.

The monastery had been founded in 1929, an answer to a plea for more priests in China that had been requested of Nève on Christmas 1926, during a visit to St. Andrew’s by the much-celebrated, newly ordained Chinese bishops: Bishop Kai-Min “Simone” Chu, Bishop “Melchiorre” Souen, Bishop “Odorico” Tc’eng, Bishop “Filippo” Tchao, Bishop Chao-T’ien “Louis” Tchen and Bishop Jo-Shan “Joseph” Hu.

The monks called their monastery Shi Shan, Chinese for Mountain of the West, in which it nestled. Although Winance knew French, Latin, Greek, English, he knew not a word, not a character of Chinese, so he had to learn the language. After a month-long rest, just before winter’s drizzle soaked monks and monastery, Winance headed – on foot – to Suining, about 70 miles.

For the next nine months, Winance made his home with the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris in their two-story priory and offered Mass in its adjoining chapel – both built in a European style that stood like palaces surrounded by a city of hovels. To pick up the everyday language of the local dialect of Mandarin, the language of mainland China, his days were filled with hours of repetition. But the real challenge came after lunch, when local children gathered around the priests resting outdoors in the chapel’s garden.

Among them was a slim, shy boy of 10, Bang-Jiu Zhou.

Zhou’s family, Catholics for who-knows-how-many generations, lived in a one-story, four-room wood structure without amenities. No electricity, only wicks soaked with pork oil gave light. Water, carried from a public well on the street corner. Bare earth served as the floor. Ventilation came from a hole in the roof above the coal cooker. Fresh air, and rain, entered from two broken windows in the loft. Property of the church, it was located on the other side of a wall behind the chapel, so close, that Zhou often attended daily Mass with his family. But on holy days of obligation, the Zhous walked several miles to the big parish church, located within the city walls.

One Sunday in August 1934, Nève, father abbot of the Benedictine monastery in Bruges, and Father Gabriel Roux, then-prior of Shi Shan, had both visited Suining. After Mass, Zhou’s father, Zi-Nan “Paul” Zhou, had an idea. Although he persevered at selling eyeglasses from his sidewalk table, with seven sons, the few yuan he earned never seemed enough. He wanted his No. 6 son to have a future. Following thanksgiving prayers, he pulled Zhou from the pew, and the two walked to the priory, where Nève, Roux and the Chinese pastor sat in the lounge, waiting for breakfast. Zhou and his father entered, kneeled before Nève and kissed his ring.

“Please, receive my son in the monastery as an oblate to study to be a monk,” Zhou’s father asked. The Chinese pastor translated for the Belgians into Latin in sotto voce.

The two visiting priests said nothing, but smiled. Four years later, in August 1938, when the monastery began accepting oblates, Zhou, at the age of 12, was one of the first. He wanted a better life, that was clear, but to be a monk, that was not clear.

Even though life inside the monastery was – on most days – peaceful, life in China was anything but, for the country had been in turmoil for years.

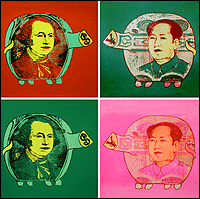

After the Republican Revolution of 1911, which ended a centuries-long dynastic rule, the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) was formed by a number of Republican cliques that had ousted the traditional rulers. But in 1927, the Nationalists – after Kai-Shek Chiang assumed leadership – ousted its Communist contingent because of its incitement and sadistic fondness of mob violence – especially at the encouragement of its ringleader Tse-Tung Mao.

But Mao, a notorious sore loser, never, ever forgot or forgave a slight. That snub in 1927 ignited the highly volatile on-again-off-again Chinese Civil War between the Nationalist and Communist factions that ravaged China for more than two decades.

However, the Communists weren’t the only problem. There was also the Empire of Japan, which saw the fractures in China’s infrastructure as an opportunity to make land grabs. In an attempt to establish their own political and economic domination, in 1931, they invaded Manchuria, a region in northeast China, where they wanted to get their hands on China’s natural resources of coal, iron, gold and giant forests. Then in 1937, the Chinese-Japanese War began when the Imperial Japanese Army marched victoriously into Peking, then into Shanghai and on and on throughout China. As part of its plan of aggression, the Imperial Japanese Air Combat Groups dispatched war planes that dropped bombs upon populated areas, killing countless Chinese.

When Japanese military aircraft crossed the Szechwan border, a high-pitched steam whistle all the way in Nanchung alerted everyone within earshot, including those in the monastery. Although several miles away, it was impossible to miss. Winance rounded up the oblates, including Zhou, and all sought safety outdoors, away from the buildings, usually under a rock or in a hole in the ground. More than once, as the planes dropped their cargo onto Nanchung, Winance listened to the descending whistles of the bombs before they exploded upon the earth.

During the height of the Japanese invasion, the no-holds-barred death match between the Nationalists and the Communists was given a lengthy timeout when Communists kidnapped Chiang and compelled him to sign a truce, creating on paper a superficial United Front in the War of Resistance Against Japan to fight the invaders.

That was the situation in China. It was a mess.

And in Europe, World War II raged. The result: no communication, no money between Shi Shan and St. Andrew Abbey in Belgium. Cut off financially from its motherhouse, the fledgling religious community had to shutter Shi Shan in 1942 and seek refuge in Szechwan’s capital city, Chengtu, where Bishop Jacques Victor Marius Rouchouse offered the Benedictines a monastery and financial help.

Slowly, the monks and oblates migrated from mountain to metropolis. Zhou moved to the new priory in July 1944. Winance stayed in Shi Shan until July 1945, when he received a short letter from the new prior, Father Raphael Vinciarelli.

“Come to Chengtu,” Vinciarelli wrote.

With his breviary, diary, bits of paper with scribbles in Latin and Greek and a few other books packed away in the same leather suitcase his Uncle Henri had given him for his journey to Shi Shan in 1936, Winance shut the door to his cell a final time. He trudged up the hill he had jogged down 10 years before, turned and looked at the monastery one last time.

I was wrong. I was very, very happy here, he thought.

Never again did he see Shi Shan.

It was a familiar journey to Chengtu. Winance hiked one day to Nanchung, where he hitched a ride on a truck, which nearly killed him when it overturned. But he made it, exhausted, and finally walked through the front gate of his new home, 172 Yang Shi Kai (Goat Market Street). One month later, on August 15, 1945, on the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, World War II ended, and with the defeat of the Japanese, the Chinese celebrated Victory Over Japan (V-J) Day.

But it wasn’t fun and firecrackers for long.

The end of the Japanese occupation also brought the end of the so-called truce between Mao’s Communists and Chiang’s Nationalists. An all-out civil war between the two ensued in an elimination battle. Mao hounded Chiang and eventually chased him from the mainland to Formosa (old Portuguese name of Taiwan).

Nonetheless, with the theophobic Communists marauding around the northern border of Szechwan, the future looked grim for Catholics. Then when Mao – the materialist messiah of the “new” China – stood at the Gate of Heavenly Peace overlooking Tiananmen Square, on October 1, 1949, and announced the birth of the Marxist monster, the People’s Republic of China – with himself the head of the beast – that was truly the beginning of the end.

But for Zhou, the theophilic Catholic, what happened in the material world mattered not to his spiritual world. On October 15, 1949, he stepped into the sanctuary of the monastery’s chapel, kneeled before the altar and was admitted into the novitiate. He dedicated his life to that Benedictine battalion in the Church Militant, his body received the habit and he received a new name:

Peter.

The final stages of the civil war continued. Throughout October 1949. Then November. In December, a constant firing of weapons outside the city could be heard inside the city. The Nationalists weakened. They couldn’t hold it together any longer. Following a two-week battle between the enemies in the countryside surrounding Chengtu, the Nationalists finally retreated. They gave up the fight, gave up the city, gave up the war and gave up the country. To Communism.

Few realized what had happened at 3 o’clock that early Christmas morning.

Winance had no idea as he mounted his bicycle around 9 a.m. and steered for a boulevard outside the city, which had turned oddly quiet. An affable sort, he wanted to spread holiday cheer and wish Merry Christmas to some Protestant intellectuals he had befriended at the Provincial Academy of Fine Arts, where they all taught. Wheeling along, he noticed freshly raised red flags flying everywhere, snapping in the winter wind and many new posters pasted on the city walls, splashed with huge, bold Chinese characters: FREEDOM OF THOUGHT, FREEDOM OF SPEECH, FREEDOM OF RELIGION.

His friends, the professors, had already heard about the change in government and were all atwitter. Unhappy under the Nationalists because of economic crises that had dominated the news during their rule, the Marxist intellectuals looked forward to a new life under the Communists, who had promised everyone everything: Everyone would be rich. Everyone would have a piano. (In reality, by the end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-76), mostly only Communist officials would be rich, most pianos would be destroyed and an estimated 77 million Chinese would be dead as a result of the regime’s orders.)

But nothing extraordinary happened at the monastery, until April 25, 1950. That night, at 9 o’clock, the monks heard the furious barking of their many dogs kept loose on the property to keep Communists out.

“Tie the dogs up,” shouted a stranger in the dark.

Slowly, deliberately, the monks calmed the dogs.

“We have an order to make a search of the buildings. Go to your rooms,” ordered a uniformed police officer, with 50 more behind him.

All the monks retreated. Behind a closed door, Winance listened to the goings-on outside his room. When he heard the clicking of gun metal in the room below, in the cell of Father Werner de Papeians de Morchoven, he opened the door to go downstairs and investigate.

“Stay in your room,” ordered an officer.

The situation in China had definitely taken a turn.

Winance returned to his room and quietly looked through his bureau. He found a photograph of de Morchoven dressed in his uniform as chaplain to the U.S. Air Force, which could cause definite trouble indefinitely. Winance immediately swallowed the photo. For six hours he stayed in his room. The officers didn’t leave until 3 a.m., after a thorough search for radios, transmitters, anything that could be used to make contact outside China. They also searched – unsuccessfully – for anything that could link the monks to the Legion of Mary, a benign, religious organization.

A year earlier, in 1949, the Communists had established the Three-Self Reform Movement, so named for its aim to be self-governing, self-supporting and self-propagating. The Movement (later replaced by the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association in July 15, 1957) was the Communist attempt to break completely with the Vatican and the Pope and to establish a schismatic Chinese catholic church.

When the Reds noticed that Catholics steered clear of the Movement, the regime decided to push their atheist agenda, and because the Legion of Mary, an apostolic association, had educated Catholics about the true intentions of the Communist-backed Three-Self Reform Movement, Mao launched a campaign of revenge. On October 8, 1951, the persecution of Roman Catholics officially began when Mao labeled the Legion as Public Enemy No. 1. Its group, counterrevolutionary. Its members, “running dogs of American imperialists.” So, too, were all Catholics who refused to cooperate and register with the Movement.

Freedom, Mao’s lie of the past, was followed by a new word whispered by everyone else: Purge.

Fear filled everyone.

Daily papers printed by the regime ran editorials of pure propaganda that were to manipulate public opinion for the Party’s purpose. Anyone who did not share the Party’s ideas was labeled an “enemy of the People,” and when “the People” (Communist officials) demanded justice, the enemies were hauled before “judges” (interrogators) and dealt with as they deemed. Consequently, freight trucks packed with the condemned, wearing big labels on their backs, ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE, headed day and night for Chengtu’s North Gate.

With tension taut, Zhou ventured outdoors very seldom, remaining in the monastery to study. On the other hand, to record for history what he witnessed, Winance continued to ride his bicycle around the city, where he noticed, at times, a certain man.

“A man of around 30 years old, clothed with the blue uniform of the ‘organized and conscious’ workers was inspecting the lorries with their load of human victims at the gate, among a roaring crowd,” Winance wrote in his diary.

“When the lorries were slowly passing the gate, the man ‘sketched’ in the air a small gesture while he looked at the lorries. That man was a priest, giving the last absolution to Catholics crouched in the lorries, all about to die. He was absolving some of his faithful parishioners lost in the crowd of ‘damned’ enemies of the People.”

Past the North Gate, a final ride across a bridge of stone, the victims were herded out of trucks and executed, usually shot in the back of the head. Their limp bodies, rolled into mass graves.

On November 4, 1951, Zhou was ordered to attend a public meeting, during which the Roman Catholic Church would be criticized. Before entering the monastery’s grand entrance hall, where the Communists ordered the meeting to be held, Zhou prepared a speech. In it, he described the Pope of Rome as the only visible head of the Roman Catholic Church, denounced the Three-Self Reform Movement as a Communist tool and defended the Legion of Mary as a religious organization.

As he wrote down his sentiments, he realized what effect his counterrevolutionary words would have on his future, which he summed up in his conclusion.

“My head is completely calm and clear. My soul is impregnated with the eternal truth of Jesus and with His inexhaustible goodness. In the final analysis, I know who Jesus Christ is. I understand where man comes from and where he goes after death. This gives me a more profound knowledge of the meaning of human life,” he said, in a clear and strong voice. He did not falter.

“Therefore, do no worry about me. Do not try to offer a hand of sympathy to save me from what are my chains of truth. I only ask you to do with me whatever you like, according to the common judgment of the masses. I deliver my body to you, but I keep my soul for the good God, for Him, who has created me, nourished me, redeemed me and loved me.”

Zhou was ready to accept his fate, and the chains.

So was Winance, who on the morning of February 5, 1952, received an order to go to the police station, where he underwent interrogation and insults. In a few hours, he found himself before the Supreme Court of the Military Government of Western Szechwan, who found him guilty of his “crimes”: that he had spread false rumors, opposed the Three-Self Reform Movement, etc., etc.

Sentence: “forever banished.”

That evening, around 6 p.m., Winance and 11 other foreigners, mostly elderly – five priests and six nuns – were marched forcibly through the streets of Chengtu and out the South Gate to walk along the old stone road. His Aunt Marta had left China years earlier. For 15 days, the political enemies were escorted by six armed guards as they traveled by foot, bus, train and boat until they reached China’s southern border on February 21, 1952. Many in the dirt-encrusted group were almost too weak, too sick to cross Lo Wu Bridge into Hong Kong, and into freedom.

Once safely on the other side, Winance wrote to his mother, “I come from hell.”

But in hell, Zhou remained. Because he was a native Chinese, he was not permitted to leave. And no one outside China heard a single word about him. Nothing. Nothing but complete silence. No one knew that the Communists forced him out of the monastery on April 26, 1952, after which he barely scraped by for a few years.

No one knew what happened to him on November 7, 1955, when he was wakened at 3 a.m. by the blare of a car horn, followed by someone pounding on the front door. He jumped out of bed, pulled on some clothes and started to answer the door on the first floor, when two police officers, each holding a revolver, ran up the stairs.

“Raise your hands,” they shouted.

For Zhou, that night he was arrested was the beginning of 26 years of torture.

Accused of crimes against the People’s Government because he had refused to join the Communist “church,” he was considered a counterrevolutionary, one who opposed the Communist Revolution, a political enemy. He was locked up and endured intense interrogations for nearly three years. At one point, his hands were cuffed behind his back for 29 days, in an attempt to get him to “reform” and give up his fidelity to Rome, to the Pope.

Zhou never gave in.

In August 1958, guards transported him to a courtroom and forced him to stand as his case was presented to three “judges,” who attempted to coerce him to admit his counterrevolutionary “crimes.” He was all alone. No defense attorney. No family. No friends. His “trial” lasted no more than 10 minutes. One month later, again he was led to a courtroom, where in fewer than five minutes he received his sentence: 20 years. After the pronouncement, he attempted to pull from his pocket a pre-written short declaration.

One of the judges jumped from his seat and ran toward Zhou.

“You needn’t read it! Just submit to us,” he screamed, snatching the paper out of Zhou’s hand.

For the next couple years, Zhou was transferred from one prison to another until June 15, 1960, when he was bused to No. 1 Prison of Szechwan Province. Upon arrival, he wrote on his registration form: “I was arrested without cause and imprisoned for the Church.” He refused to take part in the daily brainwashing “study sessions.” Prison rank and file didn’t like his “bad attitude.”

On August 10, 1960, he was summoned to the office of the section chief in charge of discipline and education.

“Do you admit that you have committed a crime?” the section chief asked.

“I have not committed any crime. I have only defended the faith of the Catholic Church,” Zhou answered.

Twice more the section chief asked the same question.

Twice more Zhou answered the same.

The section chief removed from his pants pocket a pair of bronze handcuffs and motioned for two of his assistants to grab Zhou’s arms and pull them behind his back. The section chief clicked the cuffs into place, about five inches above the wrists, and continued to tighten the cuffs, a click at a time. The right cuff, tightened almost to the limit.

For five days, Zhou endured not only the pain from the cuffs, but he had to endure harsh criticism and physical abuse from other inmates, who were forced to inflict punishment from dawn till dark or they could face the same. During an intense criticism session on August 15, 1960, someone grabbed the handcuff on his right forearm. Click. It was forcefully tightened to the fifth and last click.

Despite the pain – physical, mental, emotional – he resisted. Back in his cell, he prayed silently to Christ, to the Blessed Mother, to the Holy Ghost. He found tranquility.

In the unbearable summer heat, the cuff dug into the meat, the muscle. The rancid smell of the bloody mess stewing in his crematorium-like cell lured flies that laid eggs. When hatched, the maggots dined on his dying flesh. From the cuff down, his right arm grew completely numb, then withered. His fingers crippled, seized into a permanent claw-like grip. After four weeks, guards removed the cuffs, but clamped shackles onto his ankles.

After three years of dragging his chains, in May 1963, two prison guards summoned Zhou, all 5 feet, 1 inch and 90 pounds of him.

“Why do you not follow the example of the priest Wen-Jing Li? You must change your obstinate stand and take the path of siding with the Communist Party and the Chinese People. If you do this, you will gain a bright future,” they said.

Zhou completely rejected their suggestion; as a result, he was moved to solitary confinement.

Before slamming the door shut, they chided, “Here, you are to reflect carefully and do serious self-examination in this new situation.”

Enclosed in darkness for nearly two years, Zhou found an inner light as he reflected, prayed, meditated, composed lyrical lines of poetry.

On March 13, 1965, the door opened. Light bathed his filthy body.

“Thought reform is a long process, and you need a better environment to do self-remolding,” a guard said, removing Zhou’s iron shackles.

For the first time in five years, his ankles were free from the weight of the iron chains. It felt odd. He could barely walk. But there was never any freedom from torture in a Communist prison. For Zhou, it never ended.

For reciting one of his poems aloud, to show his unfaltering faith to God, an additional five years was added to his sentence in September 1966. On Ash Wednesday, February 24, 1971, when he refused to read the “Quotations from Chairman Tse-Tung Mao,” he was placed in solitary confinement, again handcuffed and shackled. He remained there for eight months. He spent another five months in solitary, when, on September 9, 1976, he refused to read an obituary glorifying the deceased Mao. Another five years was added to his sentence when, on Labor Day, May 1, 1977, he refused to purchase the fifth volume of “Selected Works of Mao Zedong,” with the few cents he earned for his prison labor.

But with the death of Mao in 1976, Xiao-Ping Deng rose to power. Best known as the Leader of China (1978-79), Deng opened China to the world, especially after December 1978, when he announced his capitalist reforms and Open Door Market Economy Reform Policy, which loosened the binds – a bit – that had constricted China under Mao. Some Chinese unjustly imprisoned were released.

Zhou was one of those.

On July 22, 1981, Zhou received word that his sentence would be reduced and that he would be immediately set free. At the age of 54, he packed up his few belongings. Over the years, he had been able to purchase from the prison store, small calendars, on which he had marked days of particular note regarding his imprisonment and treatment. Those, he concealed between pages of the dictionaries that he packed among his bits of clothing.

On July 25, 1981, without hatred or bitterness, he bid farewell and walked through the two iron gates to freedom. Prison officials assigned a reliable inmate to accompany Zhou the few miles to the Jialing River; once across, he spent his first night in nearly 26 years as a free man.

But almost 55 years old, he had no future. What was he to do.

Not knowing if it were possible to rejoin his monastic community, or if it even existed, he attempted contact. On July 28, he wrote and sent off three letters to St. Andrew Abbey in Bruges, and a fourth to Yu-Xiu “Pansy” Lang, an old friend of the monastery. On December 22, he learned that, yes, the monastery had survived and had reestablished itself in Valyermo, California, in 1956.

After all those years, after almost 30 years, it was possible. Yes, he would rejoin his community.

Zhou’s old teacher Winance was in Tournai, Belgium, visiting his brother André, when he received a letter from Father Gaetan Loriers, one of the monk-priests in Valyermo.

Opening the envelope and pulling out the letter, Winance read, “Brother Peter is alive.”

He’s alive, Winance thought, stunned with joy. Brother Peter’s alive.

POSTSCRIPT: On November 27, 1984, Bang-Jiu Zhou (Brother Peter) was reunited with his religious community. At the age of 58, he professed his solemn religious vows on June 29, 1985.

Zhou, now 82, and Joseph Marie Louis Stanislas Winance (Father Eleutherius), who will celebrate his 100th birthday on July 10, were interviewed extensively for this story. In addition, some facts and quotes were pulled from the unpublished memoirs of Father Werner de Papeians de Morchoven, Winance’s 1959 book, “The Communist Persuasion: A Personal Experience of Brainwashing,” his unpublished diaries (one in French, another in English) and Zhou’s autobiography, “Dawn Breaks in the East: A Time Revisited,” which may be purchased from him. Winance’s book, although currently out of print, may be found for sale online. Both published books are must reads.

Greetings and requests may be sent to: St. Andrew Abbey, 31001 N. Valyermo Road, Valyermo, CA, 93563.